The Asian community fears leaving their homes because of the unprovoked attacks and harassment. Photo by Diego Marin on Unsplash

The Georgia spa murders brought new attention to attacks on Asians and caused outrage across the country. Six Asian women were among the eight killed in the three spas in Atlanta and the surrounding areas. The violence highlighted a shocking trend: the increasing attacks and harassment against Asians across the United States since former President Donald Trump began calling the coronavirus the “China virus” and the “Kung Flu.”

Asians often don’t report such crimes to avoid more trouble, and sometimes because they don’t speak English. Advocacy groups launched Stop AAPI Hate to encourage people to report hate actions against the Asian American Pacific Islander communities. Their website is set up to receive reporting in English, Chinese and other Asian dialects. Between March 19, 2020 and February 28, 2021 they received more than 3,800 reports of these incidents across the U.S.

President Biden and Vice President Harris visited Atlanta after the shooting to meet with members of the Asian community. The president said, “The conversation we had today with the leaders, and that we’re hearing all across the country, is that hate and violence often hide in plain sight. It’s often met with silence. That’s been true throughout our history, but that has to change because our silence is complicity.” He also said, “Too many Asian Americans have been walking up and down the streets and worrying, waking up each morning this past year feeling their safety and the safety of their loved ones are at stake.”

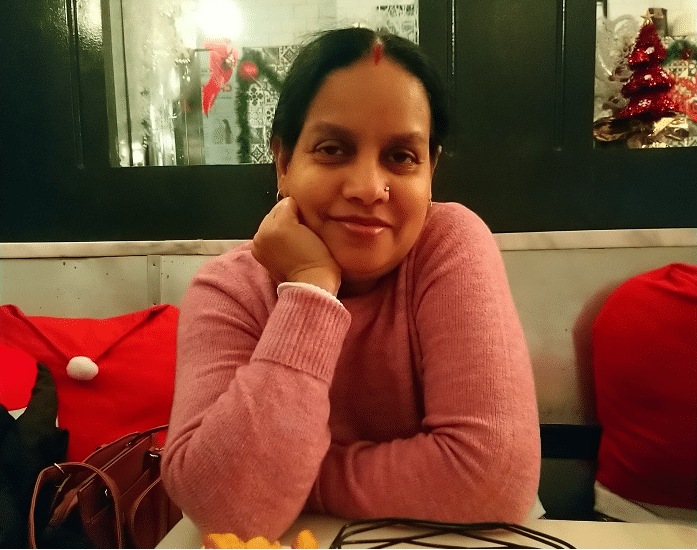

In New York, many Asians have experienced attacks and harassment, both subtle and direct. Susan Ng, a project coordinator at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, can’t forget what happened to her.

“I was waiting for the B52 bus on Bushwick Avenue with my husband when a man approached us and asked if we are Chinese or Japanese, and then started cursing us out,” she said. She got on the bus, and her husband stayed behind. The man boarded the bus and stared at her until he got off after about five stops. She was afraid and had her phone out to record in case he did anything.

After that, she began to drive instead of taking public transportation. “I am more anxious when I am out because the attacks have been so random and you never know who will be targeted next. Many anti-Asian assaults or attacks happened in the areas that I have been before, so now I always make sure I am not alone when I am out and am aware of the people around me,” Ng said. She now works remotely and can avoid public transportation, and that makes her feel safer.

In New York City, the number of anti-Asian hate crimes has risen dramatically since the pandemic started. The NYPD reported a nearly 2,000 percent increase in Asian American hate crimes last year. That is without counting unreported incidents or those that lacked sufficient evidence, like the attack on a woman outside of a bakery in Flushing, Queens in February. A man threw a box at her and pushed her to the ground. The attack was caught on camera. Police found the assailant, but the case was not investigated as a hate crime.

Like Ng, some avoid public transportation. Eiko Sugano, a manager at a Japanese soba house, bikes to work, “I feel unsafe being in the subway or bus. I would rather bike 40 minutes to work,” Sugano said.

Similar attacks and harassment happen all across the country. Many alter their behaviors to try to protect themselves and their families. Waiyi Wang lives in Brooklyn and says she won’t send her four-year-old to kindergarten in the fall. “I don’t want to send my child to school yet. I am afraid that he will be discriminated against and bullied at school,” Wang said.

But Carolina Cen, a senior studying engineering at City College, can’t afford to let fear keep her from her on-campus lab class. “I feel some people are unfriendly, staring at me when I am on the subway to school for the lab. Even though they don’t say anything, it makes me feel that I am not part of this community,” she said. She and her family try not to go out unless it is necessary, but when they do go out, they keep a close watch on their surroundings. “We are more alert about what is going on in our neighborhood and people around us when we are outside. I wish all of this could stop soon,” she explained.

Even celebrities and politicians say they have experienced discrimination.

Jeremy Lin, once a New York Knick now with the Santa Cruz Warriors G League team, said he’s been called “coronavirus” on the court. Grace Meng, a Democratic congresswoman from Queens, said she keeps receiving anti-Asian voicemail messages.

Congresswoman Meng, a member of the judiciary subcommittee, responded emotionally at a hearing on anti-Asian violence when Texas Republican Chip Roy referenced lynching as he blamed the Chinese government for the coronavirus. Fighting to hold back tears, Meng said, “Your president, your party, and your colleagues can talk about issues with any other countries you want, but you don’t have to do it by putting a bulls-eye on the back of Asian Americans across the county, on our grandparents, on our kids.”

Many like Congresswoman Meng want change. They say it begins with respect and people acknowledging the pain of the Asian community. Jeremy Lin posted this message on his social media after Wednesday’s Atlanta mass shooting: “We have to keep standing up, speaking out, rallying together and fighting for change. We cannot lose hope!”

Tags: AAPI Anti Asian hate CCNY City College of New York City College Journalism MeiJun Lei racism stop asian hate The City College of New York

Series: Coronavirus