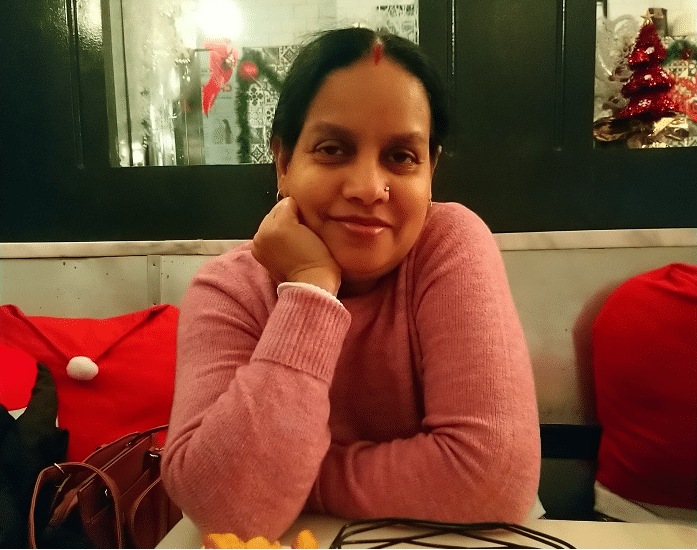

Unemployment has helped pay the bills, but Shikha Chakraborty just wants to get back to work.

CORONAVIRUS DIARIES: A SERIES

In November 2020, students in a section of an Introduction to Journalism course at City College interviewed family members about how their lives changed during the pandemic. Shikha Chakraborty is Dedipta Bhattacharjee’s mother.

It was a normal day, nothing out of the ordinary, when Shikha Chakraborty clocked in at her job at Au Bon Pain at 6:30 AM on a Friday last spring. Next week’s schedule, already posted in the office, had her name labeled for the weekday morning shifts as usual. Everything was fine until 7 AM when she received the news.

Her manager sat her down and said the words that hung over her shoulders for the rest of the day. “They told me to leave. ‘Don’t come, starting Monday,’” recalled Chakraborty, who worked in a store on the Upper East Side. “When I asked, ‘When do I come back?’ they told me they didn’t know. They told me there’s no guarantee and to apply for unemployment. I felt horrible. I didn’t understand why this happened to me.”

Three weeks later, at the end of March, Chakraborty filed her first claim, alongside millions of other Americans, receiving less than $300. “Rent haunted me. That was my biggest concern,” said Chakraborty. Assuming that her unemployment benefits would only last for three months, she was frantic. “I was worried. I calculated and organized everything. Kept track of all the spending.”

A week after her first payment, she received her first stimulus payment of $600. “It was a blessing. Because of it … I [was] able to breathe.”

Stimulus payments continued until August, but Chakraborty felt restless. Although the money placated her financial worries, the risk of her job and the uneasiness of going back to the workspace troubled her. “More than the money, I want my job back, but I don’t know if they will call me back,” said Chakraborty.

Having been a housewife for a major part of her life, Chakraborty landed her first job when she was 44 and suddenly thrown into the position of being the sole breadwinner of her family of three. Eight years later, her job has become an integral part of her identity. “Even if I wouldn’t get unemployment, getting the job would make me feel better,” she said.

Over eight months have passed since her last day of work, and Chakraborty still feels she’s walking a tightrope as, like so many others, she waits to hear about a new stimulus plan that has yet to be determined by Congress. While the prospect of her job remains uncertain, her hope shifts to a check from the U.S. government.

“The thing that’s needed—not just for me but for everyone—is not being done,” said Chakraborty. “They’ll do it today, tomorrow, the day after tomorrow, but they don’t realize they can eat and sleep in peace, but they don’t think if the people who voted for them and placed them in their positions—if they are able to eat and sleep as well.”

Chakraborty believes she’ll be able to find a new job by spring but is also considering starting her own small business. “I might not be able to, but I want to do something. I can’t stay still,” said Chakraborty “For myself, for this country, for the whole world, I wish for peace. May peace come. Everyone needs it.”

Series: COVID-19 DIARIES