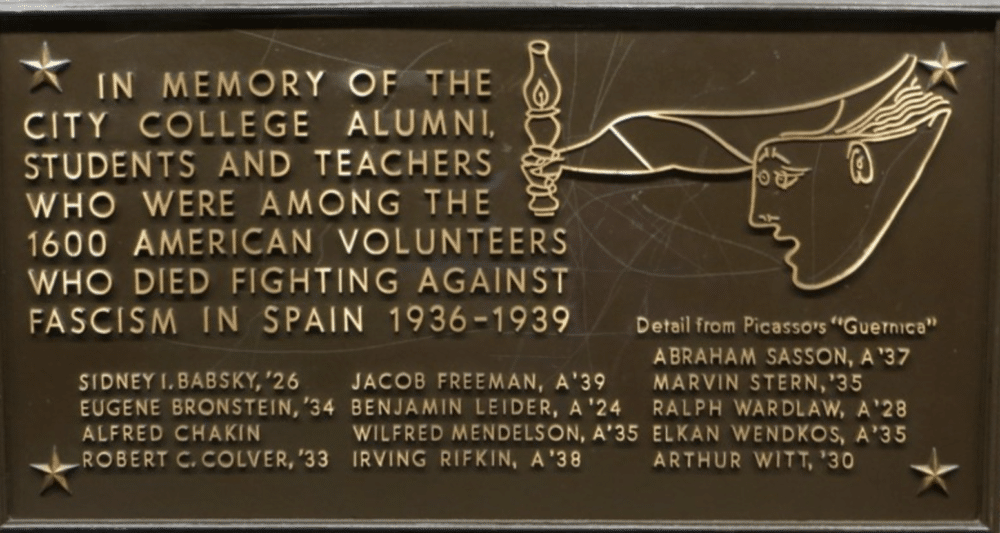

City College Professor Isabel Estrada and a team of students created a living memorial to a former student activist who left New York to fight in the Spanish Civil War in 1937. Wilfred (Mendy) Mendelson was among 60 students from the City College of New York (CCNY) who fought for the leftist Republican government against the fascist Nationalists led by General Francisco Franco. Mendelson wrote letters home detailing his experiences in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, the battalion of approximately 3,000 volunteers from the U.S. He was killed in action in 1938.

Professor Estrada is a native of Spain, and her academic work in the Department of Classical and Modern Languages & Literature focuses on the film and literature of the civil war (1936-1939). During her first year at the college in 2013, she saw a plaque in the North Academic Building honoring the City College volunteers.

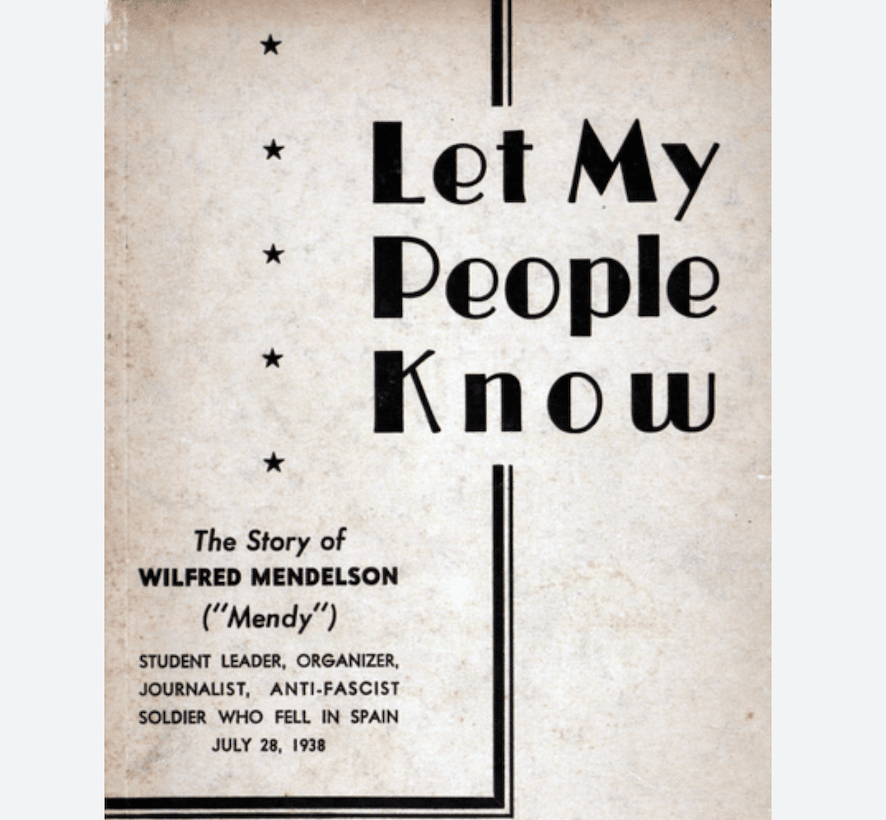

She was intrigued and looked further. “I had a conversation with the head archivist and Professor Sydney Van Nort in Cohen Library, who told me that a few years back they had an exhibit about those volunteers,” Estrada said. Prof. Van Nort helped her find a book entitled Let My People Know. The Story of Wilfred Mendelson, “Mendy,” August 17, 1915 – July 28, 1938, which included Mendy’s biography, the letters he wrote to family and friends from the Spanish Front, and two political essays. These materials were originally compiled by his classmates in 1942, four years after his death in Spain.

Everything Estrada read in the book excited her. “His writing reflects very mature thinking and a very engaged young man,” she said. She felt inspired to edit the material and turn it into a digital book that could become available to a wide audience. “I was very impressed with the level of political engagement of that generation,” she continued. Estrada wanted to make sure that students now and in the future have the opportunity to see how politically engaged Mendy and the others were. “I hope there is a greater appreciation for what that generation and volunteer students did,” she said.

With the support of an NEH grant, she designed a class called Activism and the College Experience and enlisted Stefano Morello, a Ph.D. candidate in English, to teach Digital Humanities tools to the students. In spring 2022, the instructors and the students examined ways to expand it and give it more context. Melonie Matonte, an Uruguayan-American, joined the class and helped organize the letters and provide historical context for what Mendy described. It surprised her that Mendy was only 17 years old when he was at City College, and yet he was passionate about political activism and was expelled because of it. Matonte admired the way he and other young people mustered the courage to put their passion into action off campus: “Mendy’s story is one of direct action that could inspire other people his age today.”

Like many City College students of the time, Mendy was the son of Eastern European immigrants. He became active in the Jewish socialist labor movement, and his writing warned about the dangers of rising fascism in Europe. In the book, his classmates said that Mendy frequently led student protests against fascism in Europe, New York, and throughout the United States.

Mendy’s big clash with the college came on October 9, 1934. City College President Frederick B. Robinson invited a group of young Italian fascists to speak to a student assembly in the Great Hall. Mendy and twenty other students led a protest, and Robinson dismissed them all as “guttersnipes.” Students went on strike the following weeks, wearing buttons that said, “I am a Guttersnipe.” “I fight fascism.”

Over the next few months, more than 4,000 New York City college students joined their protests. Mendy wrote about it for the Metropolitan Student Weekly and didn’t let up. In February 1935, the college expelled him.

But Mendy did not give up. He joined the Young Communist League (YCL) and wrote for its newspaper, and in the summer of 1937, he left to fight in Spain. He continued to write, and in one letter to his friends in the YCL when he was only 20, Mendy said, “We deeply sense the honor to stand to the fore for democracy at this great crisis for all humanity. Whether or not we come through the hard struggles that lie ahead, we are fully conscious of living life to its fullest. There can be no regrets, only supreme joy.”

Mendy was killed in action later that year in Spain. Before he died, Mendy’s predictions came true. Hitler came to power, Mussolini ruled Italy, and Franco was winning in Spain.

Mendy’s story showcases a generation of young people who dared to make a change in the world.

“To think that these were 20-year-olds who would organize protests on campus, and some of them were expelled for and or suspended for their activities. And then that they would feel so strongly about their cause that they would just leave their families to fight in a country that they didn’t know, that was miles away,” Professor Estrada said. She reflected on the generational difference between the students, and what she hopes the impact of Mendy’s story is: “They were defending democracy, freedom of speech, basic rights that we take for granted now. And now what I see is that the majority of the population is not politically engaged and sometimes we feel like nothing we do would matter. That our role in democracy is to vote every November. But other than that we feel powerless somehow and I think that should change.” Estrada said.

Mendy’s mother, Gertrude Mendelson, wrote the original book’s closing note. In a letter, she said, “Only the research students will know of Frederick B. Robinsons, the Francisco Francos, the Pierre Lavals, and Hitlers. You who know the men of Mendy’s mold write about them; you in other communities write the tale of our men. If this booklet inspires you to do that we are happy. There were some who said in the early anguish of the news of Mendy’s death that it was in vain. No one says so now. This is the way fighters live and die. This is the life of an American, and a Communist. There was no truer or happier path for him.”

You can find Mendy’s story and the work done by Professor Estrada’s class on Manifold, Let My People Know: The Story of Wilfred Mendelson (Mendy).