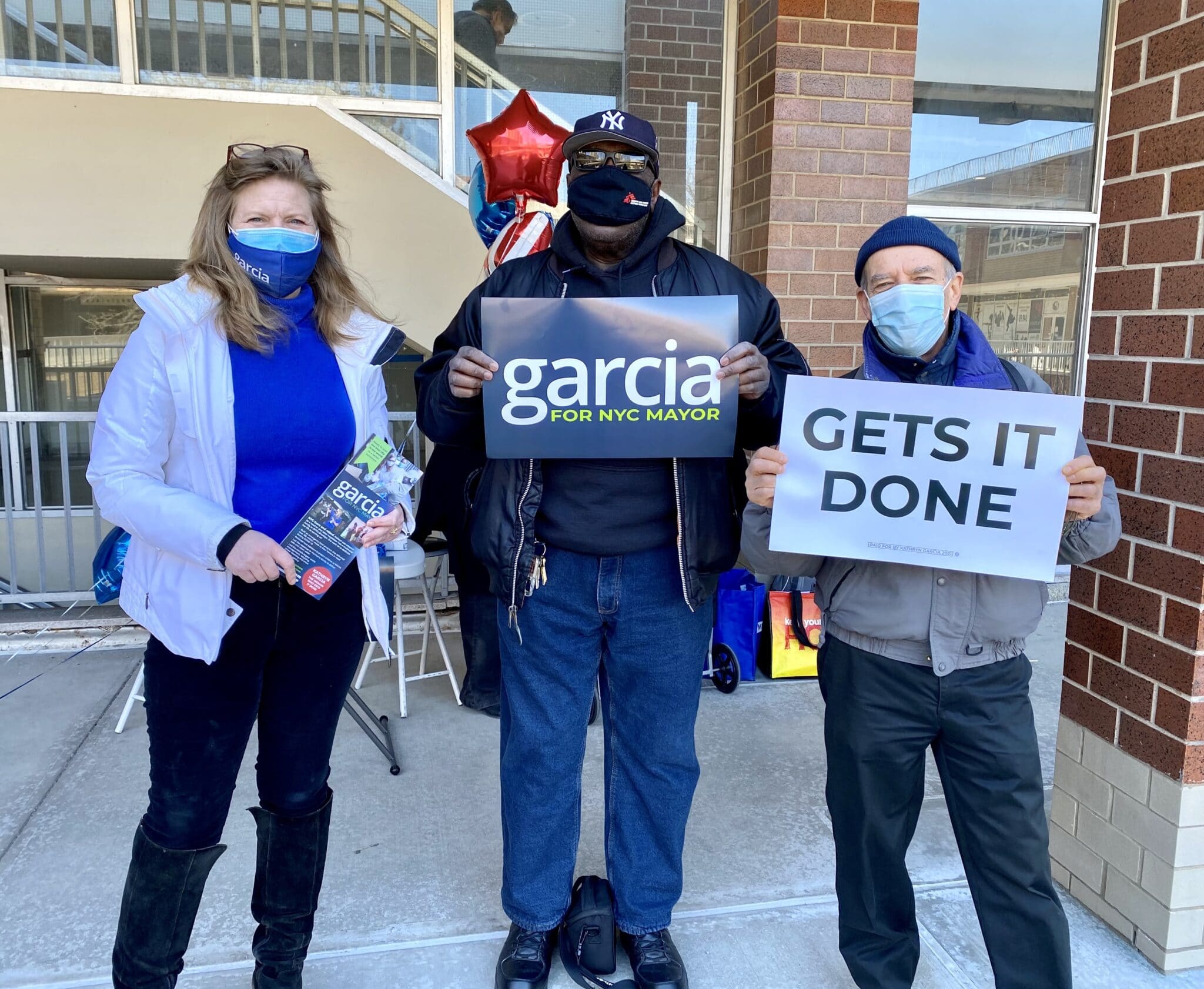

New York City mayoral candidate Kathryn Garcia is committed to restoring the sanitation budget that was cut last June.

Since COVID-19 hit New York over a year ago, residents of Harlem and Hamilton Heights have noticed more trash in the street and a surge of rats. Sul, one of these residents, said he’d like to see change in the city. “Something about the rats, somebody’s got to clean them up.” The garbage that’s allowed to spill out of trash cans and onto the streets makes a quick and easy meal for disease-carrying rats, mice, and even raccoons. “Since the pandemic, our neighborhood has gotten pretty dirty,” Edmond, a father out with his family in Riverside Park said. The Sanitation Department suffered a $106 million budget cut last June, which caused a reduction of trash collection. But with a new mayor taking office this year, there could be change afoot in the city.

Former Sanitation Commissioner and mayoral candidate Kathryn Garcia responded to some of Sul and Edmond’s concerns in an email to HarlemView. “You can’t have a functioning city and bring back this economy if people don’t feel safe, and if they don’t think that it’s clean. I will immediately restore that budget fully and reinstate the programs that have been cut.”

Reinstating corner trash can pickup is only the first step in improving the quality of life in the city. Garcia is also focused on waste reduction. Easing the amount of waste produced helps to keep services from being overwhelmed. The pandemic has demonstrated how the infrastructure fails once too much trash is thrown out at once. Some cities want to make manufacturers responsible for the waste their products produce when they’re thrown away. Garcia supports this program, called Extended Producer Responsibility.

Garcia plans to add what she calls “containerization” to the streets. Replacing curbside trash piles with large containers that store the trash until it can be collected. “We need to use our curbside space for public amenities to improve New Yorkers’ experience of their city.” She says that this plan will help to integrate sustainable infrastructure, create opportunities for small businesses, and in turn provide a boost to the economy.

Trash collection isn’t the only community concern in Harlem. “At the peak of COVID there are more people sleeping on the train and on the streets,” said Tataina Simpson, a local childcare worker, “and I think that what [city officials] could possibly do is create more housing for them. Come up with plans where people can get help.” Many empty storefronts and churches in the neighborhood have become homes for those looking for shelter.

Not all Upper Manhattan residents share Tataina’s sympathetic view of the homeless crisis. Steven was more concerned about the public safety risk. “I think homelessness is number one. I don’t see how anybody thinks that people are going to come back into the city, how we’re going to have tourism, how we’re to recover and use the subways if people are getting pushed onto the subway tracks.”

New York City spends over $3 billion annually on homelessness services, and yet over 4,000 people still sleep on the street. “These band-aid solutions don’t work,” said Garcia, who hopes to shift toward prevention using the Family Homelessness & Eviction Prevention Supplement program (FHEPS). “New York’s City FHEPS rental assistance program provides temporary vouchers to at-risk households, but the voucher amounts are often too low to rent an apartment. Fully funding CityFHEPS means less homelessness in the first place.”

The new mayor will have to face questions from a city that has felt the full force and weight of the deadliest pandemic in living history. Edmond, the father we met walking in Riverside Park, is ready for change. “It’s sort of old-fashioned bread and butter politics, but a mayor who could make sure that our trash got taken out would go a long way.”

Tags: Adam Burby Budget Cuts City College Journalism CityFHEPS Coronavirus COVID-19 Cuny Homelessness Kathryn Garcia Kathryn Garcia for NYC mayor Mayoral Candidate Mayoral Race NYC Politics The City College of New York Trash Pick-Up

Series: Elections