Vacant restaurant. Photo by Susan Thorson

In early September, a chalkboard sign appeared in front of a Mexican restaurant on Columbus Avenue and 93rd Street that read: “Gabriela’s is closing. Thank you for 15 years at this location.” In an email message published by The Westside Rag, Gabriela’s owner Nat Milner explained, “Minimum wage to $15 in three short years presented a huge challenge.” He went on to say that despite cutting staff, costs were too high to survive the upcoming slow winter.

The road that led to Gabriela’s demise began with a signature more than three years earlier. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo signed legislation in April 2016 raising the wage for non-tipped employees in New York City. The increase went up gradually to $15 by the end of 2018. Other states also moved to ensure higher pay for workers. California passed similar legislation. Washington, D.C., Massachusetts, New Jersey, Illinois and Maryland followed the trend and raised their minimum wages to $15 but will phase them in from 2020 to 2025.

While the wage increase sounds good on paper and has delivered more take-home pay to an estimated 3.1 million workers in New York State, the ripple effect forced some employers, like Gabriela’s Nat Milner, to lay off staff and fight to stay in business.

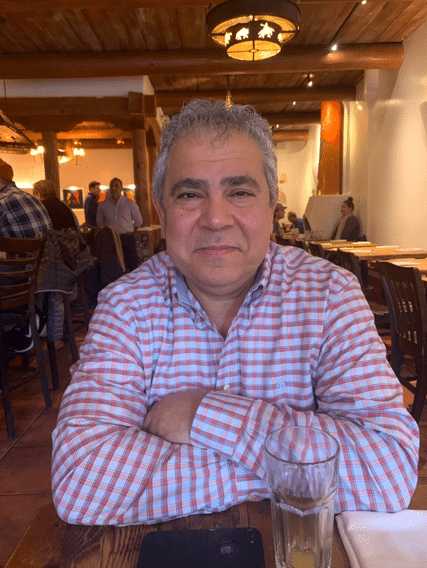

At Saad Saad’s Mexican restaurant Cilantro at 83rd and Columbus, waitstaff, rather than a host, escorted customers to their tables. Saad only needs a host for their rush, which is about two to three hours a day.

After twelve years in business, the pay hike forced him to limit the number of overtime hours his employees work. Many of his employees picked up second jobs as a result.

Saad shook his head and said, “From eleven to fifteen dollars in two years—that’s a big jump. How long can we do it? I really don’t know. If we don’t do the necessary volume, it will be impossible for us to survive,” Cilantro’s labor cost is at 40 percent. It should be about 32 percent. He predicted this may be the end for the casual dining restaurant with table service, and restaurants will lean more to counter service and use tablets for orders. “The money has to come from somewhere. And there’s only so much you can ask customers to pay. You just have to find a way to survive until you can no longer survive. What happened to Gabriela’s is going to happen to other restaurants,” he said.

Consistent with Saad’s prediction, Karina Oshiro’s counter service coffee shop, Common Good, is doing well.

The restaurant at Frederick Douglass Boulevard and 149th Street opened in July of 2018 with employees earning $13 an hour. So the jump to $15 an hour was manageable. Even so, Karina said, “Labor is high. I’m trying to keep it down. I’m working sixty hours a week to keep it down.”

Similarly, thirty blocks south, Nick and Petrushka Larsen opened Sugar Hill Creamery, a counter-service ice cream shop at Lenox Avenue and 119th Street before the wage hike. “From the beginning, we wanted to pay our staff a living wage,” Nick Larsen said. But to handle the high labor costs, he works a lot of hours. “I can’t staff as many people, so I have to pick up the slack.”

The increase affected small businesses in all fields. Book Culture, a family of independent bookstores, is fighting to keep its doors open. Owner Chris Doeblin opened his first location twenty-two years ago and has turned to the community for financial help through a Community Lending Program. “In 2016 when they passed this bill, we did a forecast putting new wages into our construct with the number of employees we had. It showed that we were going to immediately lose money in 2017, then lose a lot of money in 2018, and then just get crushed out of business pretty quickly in 2019 when it went to fifteen dollars an hour. The only way we could change that was to dramatically cut costs, which meant cutting people from our payroll,” Doeblin said. He hoped to keep his employees, so in order to grow and generate enough sales to offset the increased labor costs, Doeblin opened a fourth location in Long Island City. But the plan didn’t work. “We spent a lot of time losing money trying to grow faster,” he said.

Doeblin sees additional issues with the wage increase. He said there are thousands— perhaps hundreds of thousands— of workers in New York City who are paid cash, off the books. “This kind of minimum-wage stress gives businesses that cheat a huge incentive. You’re driving more and more people not to serve the overall tax plan that we’re trying to resolve here,” he said.

Doeblin, Saad and other small business owners face an additional challenge. They have to figure out how to handle the next level of pay increases for employees. “Everybody wants to make more money. And it makes sense. It makes sense that the person who started working yesterday should not make the same amount of money as someone who has worked for two years,” Saad said.

Despite the challenges, bookstore owner Doeblin remains optimistic. “Fundamentally, optimism is part of the cure. There is no cure without optimism. So I’ve protected that kernel, and embedded it deep in my heart,” he said.

Tags: $15 minimum wage Book Culture Chris Doeblin Cilantro Common Good Community Lending Program Karina Oshiro Nick Larsen Petrushka Larsen Saad Saad small business owners Sugar Hill Creamery Susan Thorson Upper West Side small business