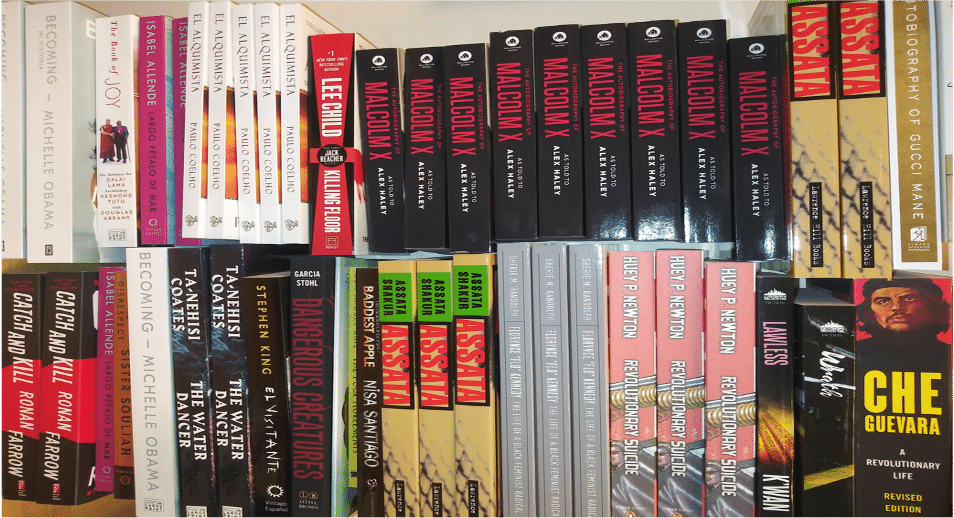

With library budgets cut during the pandemic, not-for-profit organizations have stepped up to provide books for people in New York City correctional facilities. Photo by The Prison Library Support Network.

“In reality how can you measure in numbers the impact a single book can have on a person’s life?” Emma Eriksson, director of the Prison Library Support Network (PLSN) asked.

The group works with public libraries in the city that offer services to incarcerated people and others in need. The organization says it aims to bridge the “information gap” and provide books to people who often can’t get them.

The idea to start PLSN began with students in Pratt Institute’s School of Information. They realized students in private schools had access to more books and information than many, including people on Rikers Island.

During a class project, students began corresponding with incarcerated people on Rikers Island who needed information. They answered specific reference questions and established good relationships with librarians who staff the correctional services branches of the city’s libraries. When the Pratt project ended, students wanted to continue working with the librarians.

They formed PLSN as a non-profit, and since 2016 the group has donated more than 1,600 books and raised more than $12,000 to purchase books and materials. The importance of books in Department of Corrections facilities, with its population of 5,000 people is highlighted in

Connections, a New York Public Library online publication. A formerly incarcerated writer, John Bunn, wrote that a library book that he read in prison had a profound effect on him. “I picked up The Coldest Winter Ever by Sister Soulja, the first book I ever fully read. From the onset of reading that first novel, I felt a human connection that allowed me to see my world in a new perspective. A human perspective that kept me from feeling like the walls were talking to me and moving closer.”

But the pandemic has hurt the libraries’ correctional services. The budgets of New York City libraries shrunk and money to supply books, run mobile libraries and provide services disappeared. In addition, librarians can’t visit prisons.

So PLSN decided to work with libraries in a different way. “When the pandemic hit and money became scare and tight, and we said all right we can help fill that gap. And that would include homeless shelter outreach, transitional shelter outreach and the prison populations,” Eriksson said.

But the group is still committed to serving incarcerated people It wants to raise money to build libraries in jails and shelters when the pandemic ends.

Tags: advocacy books City College Journalism donated books incarceration jails libraries libraries in jails marginalized populations not-for-profit Prison Library Support Network resources for incarcerated people