Passengers waited seventeen minutes for a crowded Washington Heights Riverside Dr Bx6 Bus on a cold day in March. When the bus finally arrived and the the backdoors opened, people at the curb rushed to get on without paying. But six police officers physically blocked their way. Another officer talked with the bus driver, and waved his hand to encourage the people outside to come to the front of the bus, board and pay. In the meantime those on the bus groaned and rolled their eyes. A lady on the bus sucked her teeth and exclaimed, “We’re all going to be late to work! Are you serious, who cares?”

The bus took four minutes and 37 seconds to leave.

Some think the enforcement is a good idea. “We need to make rules again,” said Raul Flores, 43. He uses the bus every day to travel from The South Bronx to Lower Manhattan. He wasn’t surprised that the increased police presence commuters have seen in Manhattan now reached the Bronx. “It was only a matter of time before the same order was implemented uptown,” Flores said.

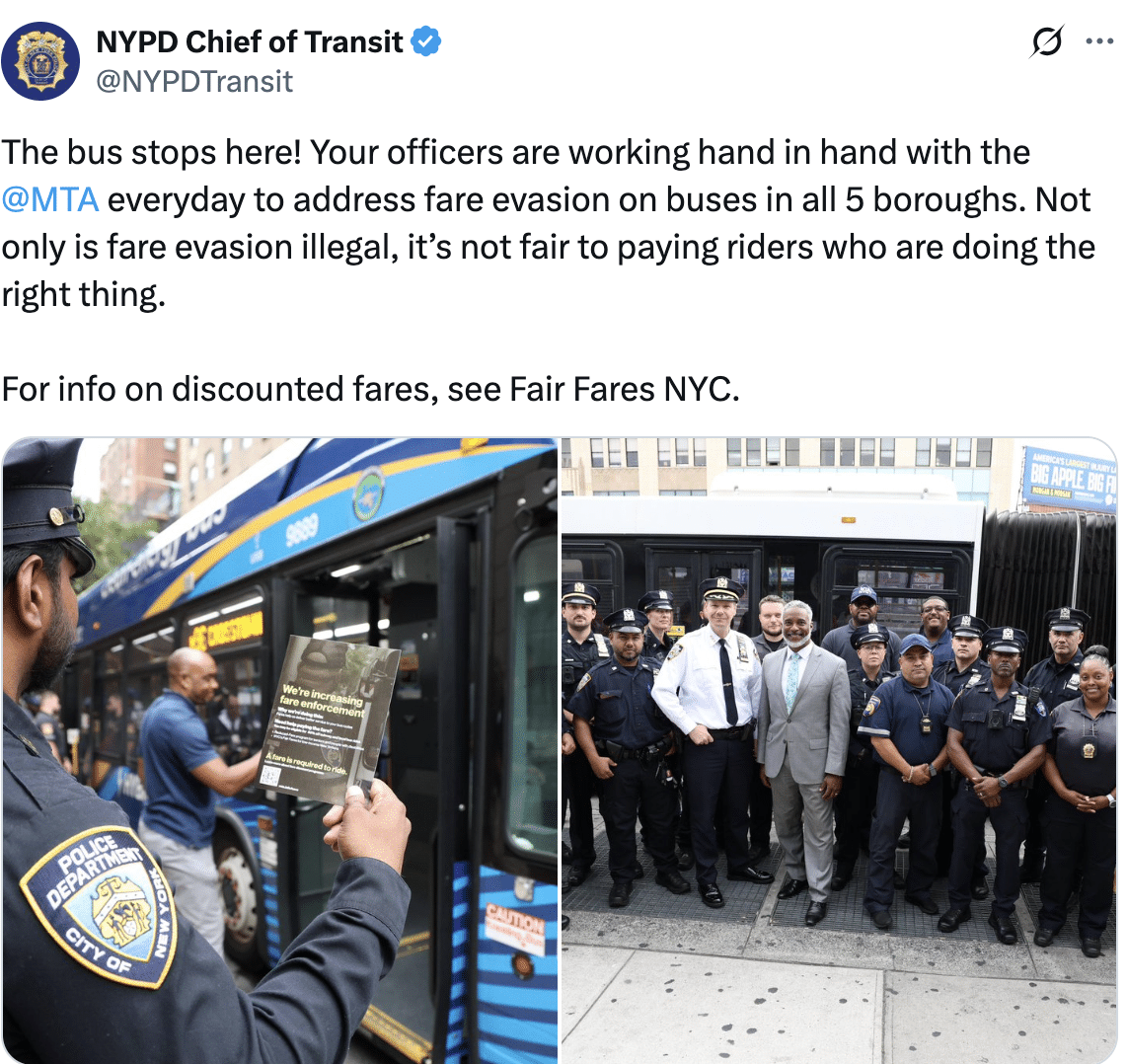

The perception is that crime has been rising, but as of January 2025 subway crime has dropped by 36.4 percent compared to 2024. Mayor Eric Adams and Governor Hochul rolled out a new initiative in January 2025, to expand security in the subways. The plan, which includes deploying 300 uniformed officers to patrol trains and stations, aims to reassure passengers and workers.

Governor Kathy Hochul shared a progress report in April 2025, showing that the overall fare revenue has also increased up to “67 percent compared to 2021” as a result.

About 3.6 million people ride the subway every day and another 1.4 million uses buses, according the MTA. While the crime rate has decreased with added security measures, people have raised concerns about the impact on the rider experience and the city’s relationship with law enforcement.

“After they started saying they’re going to start forcing people to pay, I started paying,” Flores shrugged. “I wish to pay a little bit less because everything is so high and the salary doesn’t match.”

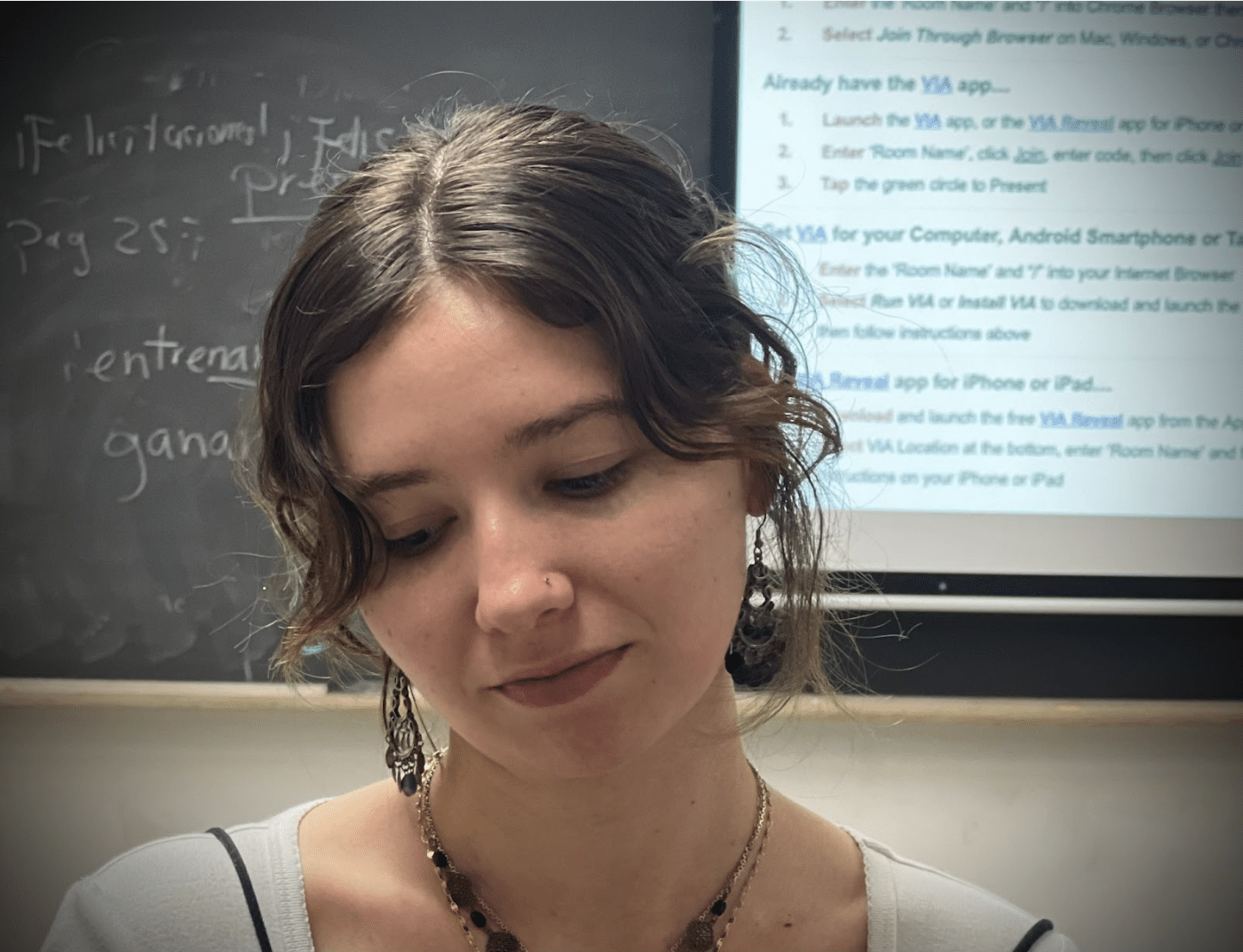

Others agreed with him. “Where I’m from, it’s only $2.75. So it was a shock to me to know that it was $2.90 when I first got on the bus here,” said Melanie Oriana Perez, a student who travels to City College from Poughkeepsie. She said that she feels indifferent about the increase of police presence at subways or bus stops. “I recognize that they’re there, but it’s more that they’re kind of taking up space and asserting dominance over people. Rather than actually feeling like they actually care about everyone’s well-being. It’s a little obvious that it’s like money hungry to just be worried about [fare evasion],” she said.

Governor Kathy Hochul and the legislature passed a 2026 New York State Budget, which includes investing $77 million in state funds to cover additional NYPD overtime on “every overnight subway train.”

Stylianos Psyllos Machado Filho, a flight attendant from Greece, tries to avoid using public transportation when possible. He likes to walk to his favorite places including the nearest movie theater or store. “When I first moved here I had economical problems. I ended up asking people if they had an unlimited card when they were getting off at the station. I was like, ‘Do it for me, please’ and then indeed there were some people willing to help me. Now I pay.”

New York Mayor Eric Adams defends the enforcement. He told Jonesy in the Morning on Hot 97, “The goal is not to be you know heavy-handed but the goal is to send a strong message. Everyday New Yorkers struggle they find that MetroCard and it’s just not right to increase the fares based on those who just don’t feel they should have to pay their share of their transportation.

But many low-income New Yorkers think strict enforcement to make people pay for bus and subway rides is unfair. While the city does offer programs for reduced fares for New York City residents living at federal poverty level, only a third are accepted. “A New Yorker who works full time at the minimum wage ($16 per hour) makes too much to qualify,” said Vice President of Policy Research and Advocacy at CSS , Emerita Torres.

Some like flight attendant Psyllos worry about the potential for over-policing in the city’s most diverse communities. He lives in Harlem and said, “We have a lot of officers doing basically nothing. Instead of chasing real criminals, they are chasing people who don’t pay $2.90 for the subway.”

To avoid paying, groups of people develop impromptu strategies. Often as many as 15 people wait for a bus at the back door and they jump on when it opens. That makes it more difficult for officers to single out one person for a fine.

Others go their own way. “I try to do my own plan. That is not paying the fare,” said Juan Pablo Medina-Verdugo, a commuter from Queens Village. Occasionally he takes the subway to work But also often drives. Medina said the increased enforcement bothers him. “It’s a scam because it’s not just about being safe, it’s also about being comfortable. I will pay if I actually feel safe. But I don’t. So I don’t,” he said.

The city and the MTA plan to continue to keep up the pressure to get everyone who rides to pay. Demetrius Crichlow, NYC Transit president said, “The strategies to improve fare collection are working. We are glad to see these efforts begin to pay off and expect to see further improvement as we expand on these initiatives and work with NYPD to keep up enforcement.”

Series: Subways, Police and The People