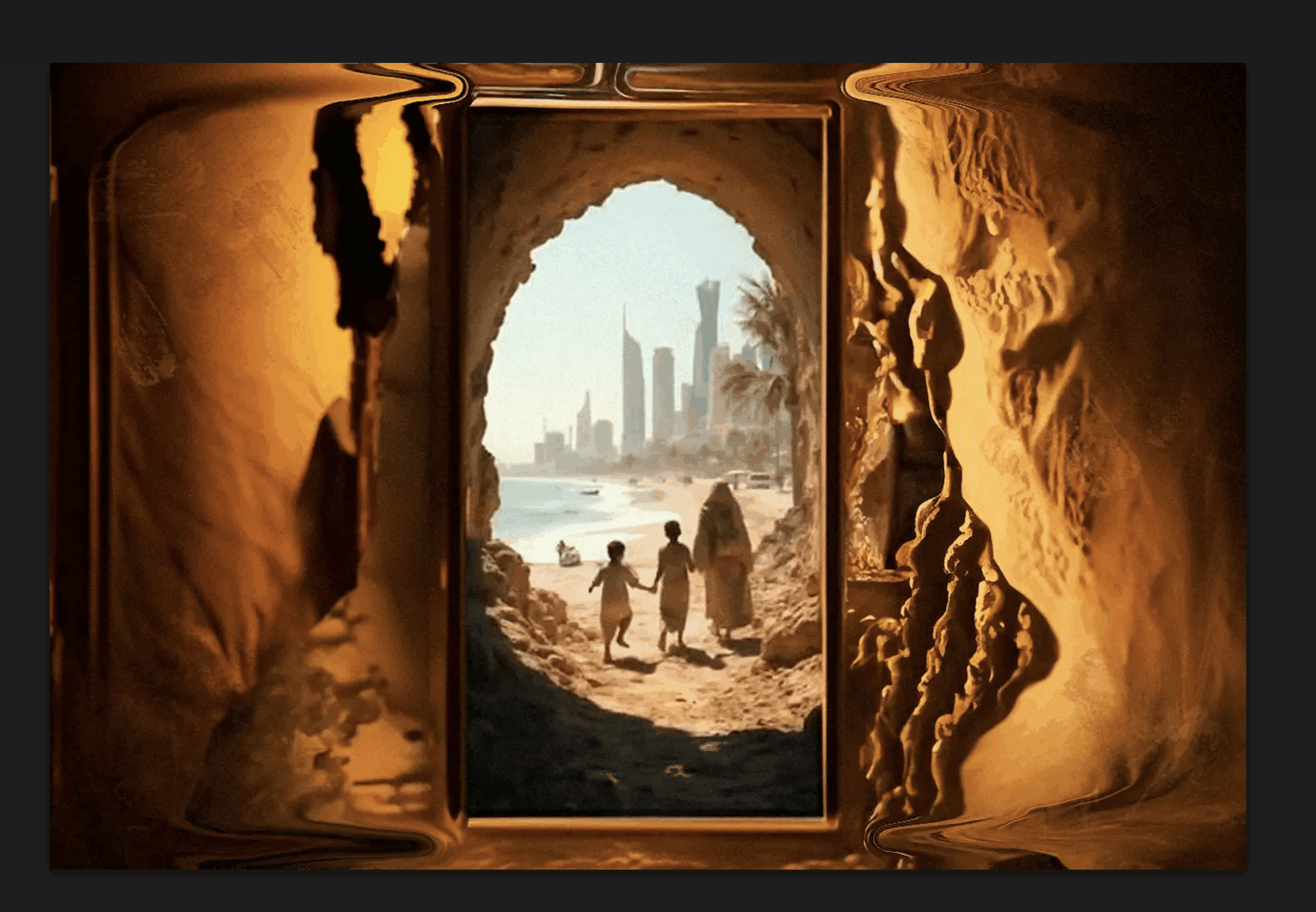

A recent young Venezuelan immigrant, one of 21,000 who recently arrived in New York City, painted the place where they wished to be. Photo by Astra Montanez.

On the second floor of a small therapy office in Woodside, Queens six children sat around a round wooden table, bringing a white square of paper to life with watercolors. The volunteer leading the art class had asked them to paint the place they wished to be. Mothers flowed into the room once the group therapy session ended to see their little ones.

“Mami! Mami! Mira lo que hice! (Look at what I did)” said an eight-year-old boy running to his mother. The mother stared. Her eyes filled with saudade (longing). She kneeled down to look at the Venezuelan flag he had painted and pulled her son into an embrace. “This is a safe place for them after all the trauma they’ve been through,” said Rosa Caballero, co-founder of the non-profit organization, Venezuelan Alliance.

The 28-year-old mother didn’t want us to use their names. She and her son were a part of the recent wave of 21,000 Venezuelan migrants that arrived in New York City. Volunteers and non-profit organizations like the Venezuelan Alliance have provided services to help. “It’s not like other established immigrant groups. Venezuelans often feel isolated or alone,” Caballero said.

Since 2014, Caballero has helped a number of victims of gender-based violence. She has worked as a licensed clinical social worker in New York to counsel migrants who arrive with migration trauma. Venezuelan Alliance provides mental health services with support group meetings at least once every two weeks so that Venezuelans know they are not alone. It also offers food, water and sometimes rent money.

The mother and son who attended the art class had traveled across eight borders for a month to come to the United States. “I traveled with rape victims,” said the mother, unease in her voice. She and the others witnessed the horrors of traveling through Columbia, the Darién Gap and Central America. She carried her son on her back as the rough trails wore holes in the soles of her shoes. “There were days I didn’t have food and my body would be in a lot of pain. At the same time, I had to have all eyes open because you never know if someone bad was near,” the mother said.

She came to New York with the trauma of being in life-threatening situations, trying to protect her son and herself as they traveled. The United Nations Children’s Fund found that women and children are at higher risk of abuse and sexual assault along their migration journey and where they settle. “No quiero que ninguna madre o niño viaje con miedo de ser herido o asesinado (I want no mother or child to travel in fear of being hurt or killed),” she told us.

The majority of the people the Venezuelan Alliance helps were victims of domestic violence, and that’s one of the reasons they fled. “In many countries, women are not seen as full citizens. Men feel they have the right to impose their power and privilege against women,” Caballero said.

The mom and her little boy have found a temporary home at a Jackson Heights shelter. They are among 20 families receiving help from the Venezuelan Alliance. The group supplements what the shelters offer, and it provides MetroCards so that people can travel without jumping the turnstiles and getting involved with the NYPD.

The non-profit also wants to help with the legal path for asylum seekers.

“We plan to push courts to move faster with the legal process for these asylum-seekers so they can contribute to our economy and find a home here in America,” Caballero said.

She and others in the organization know they need to raise more money to support the work and make a difference for these families. “We are needing funds so we hope to have a fundraiser the first week of December,” Caballero said.

Tags: Astra Montanez Astra R. Montanez Asylum Seekers CCNY CCNY Journalism Cuny legal aid non-profit shelters The City College of New York Venezuelan Alliance Venezuelan Asylum Seekers

Series: Community