DACA provides some opportunities to young people, but it does not give them legal status, leaving them in a precarious immigration position. Photo by Elias Castillo on Unsplash

Jasmilkis Santos looks over her shoulder a lot. “I think about my immigration status on a daily basis because I have to be extra careful. I can’t do anything wrong. I’m not like everyone else who can be a rebel.” The 22-year-old Queens College psychology major gained legal status through DACA, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, when she turned 14. “If I’m approached by authority and they ask for my identification—it literally says that I’m not legal here,” she said.

President Biden is taking action to undo efforts by the Trump administration to dismantle, or at least water down, DACA. He plans to reclaim America’s values by modernizing the immigration system. The executive order prioritizes “keeping families together, growing the economy, responsibly managing the border, and ensuring that the U.S remains a refuge for those fleeing persecution.” Essentially, it allows undocumented individuals to apply for temporary legal status. It also gives them the opportunity to apply for green cards after five years, if they pass criminal and national security background checks and pay their taxes. The Biden policy aims to create an earned roadmap to citizenship.

People like Santos with DACA status feel skeptical and question whether they will ever gain legal status. “I always think about how lucky I am to be in this program considering that the criteria are so specific. I’m able to work and go to school. It seems normal, but that’s crazy to me.”

President Obama launched DACA in 2012. It brought joy and opportunity to a lot of young people without legal status. People who immigrated to the United States as children and who met specific guidelines could apply and become eligible to work. It also allowed people without previous legal status to attend school and apply for loans without fear of deportation. But it did not make them citizens.

However, 24 percent of Americans opposed DACA as of 2017. Republicans railed against it because Obama created the program through an executive order after Congress failed to pass the Dream Act, which would have given young immigrants legal status. Changes in immigration law, they said, should come out of congressional legislation.

But the program made life a lot easier and safer for hundreds of thousands like Santos. She qualified because her mom brought her to the United States from the Dominican Republic when she was two. Her brother followed soon after and also became a DACA recipient. Her older sister, however, was not so lucky. She arrived in America but was sent back to D.R as a child.

Legal status, for Santos and others, became a lot more precarious after President Trump took office. In 2017, he ordered the end of DACA, to remove protections offered by the program. Under his administration, the DACA stopped accepting new applications and refused to allow recipients to renew their applications.

In January 2018, a federal court issued an injunction that forced the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) to accept renewal applications. Still, new DACA applicants were not able to apply. Finally, the Supreme Court ruled, in a 5-4 decision, that President Trump’s cancellation of the DACA program went against the Administrative Procedures Act and that the DACA program should remain.

Nathaly Camila Ardiles worried all during the Trump administration. “I felt like I was in immediate danger,” the 25-year-old said.

Ardiles received DACA status at the beginning of the program. Like Santos, she leads a relatively stable life in the United States. But Ardiles had a personal crisis at the beginning of the Trump era. She wanted to visit her sick grandmother in Peru. She applied for special permission to leave the U.S. and return but worried constantly about the security of her immigration status.

Ardiles only stayed in Peru for ten days because she feared that she would not be able to return to America if she stayed longer.

“It was a really toxic time for me,” says Ardiles. “There was nothing I could do but wait for something bad to happen. I even remember asking my boyfriend if we should get married.”

She feels traumatized by the shaky program and hesitates to believe that President Biden will finally straighten out the immigration mess for her and others who came here as children.

Ardiles and Santos, like many young people dependent on the immigration system to give them legal status, hold their breath as Biden closes his first 100 days in office.

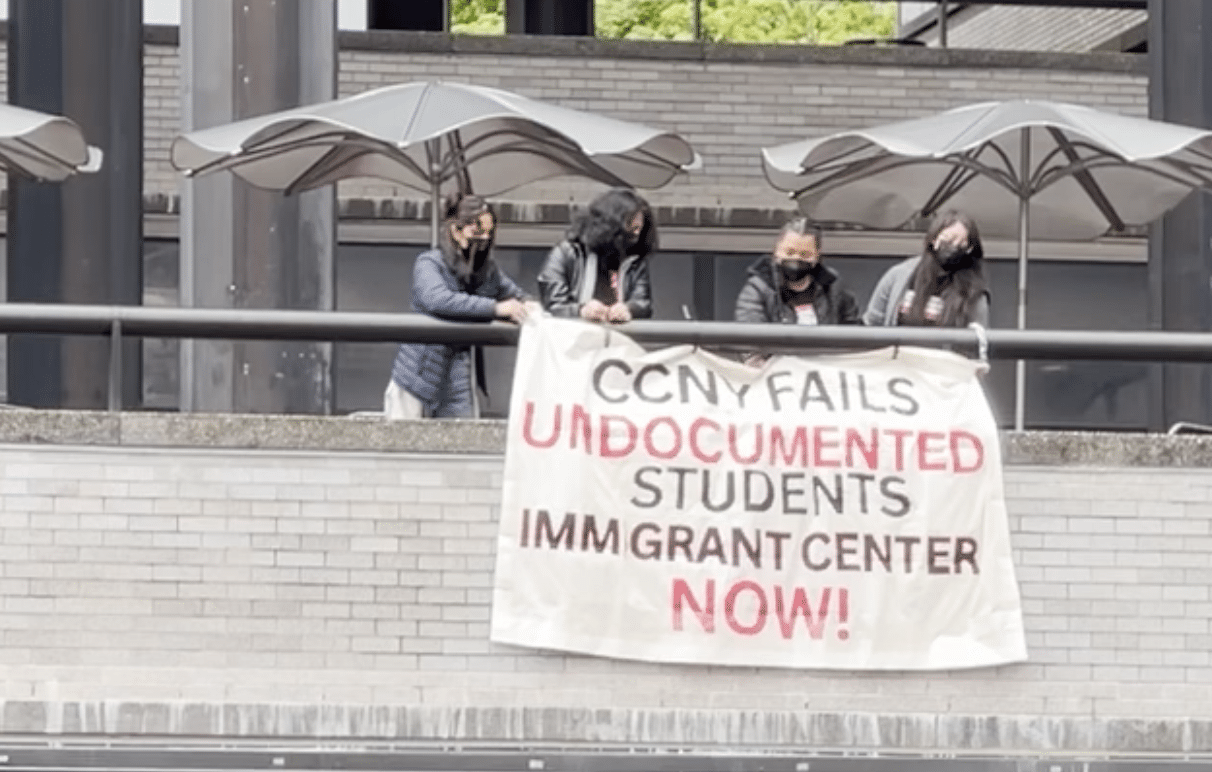

Tags: City College Journalism DACA Immigration Legal Status Teresa Mettela The City College of New York