Photo by Emma Montero

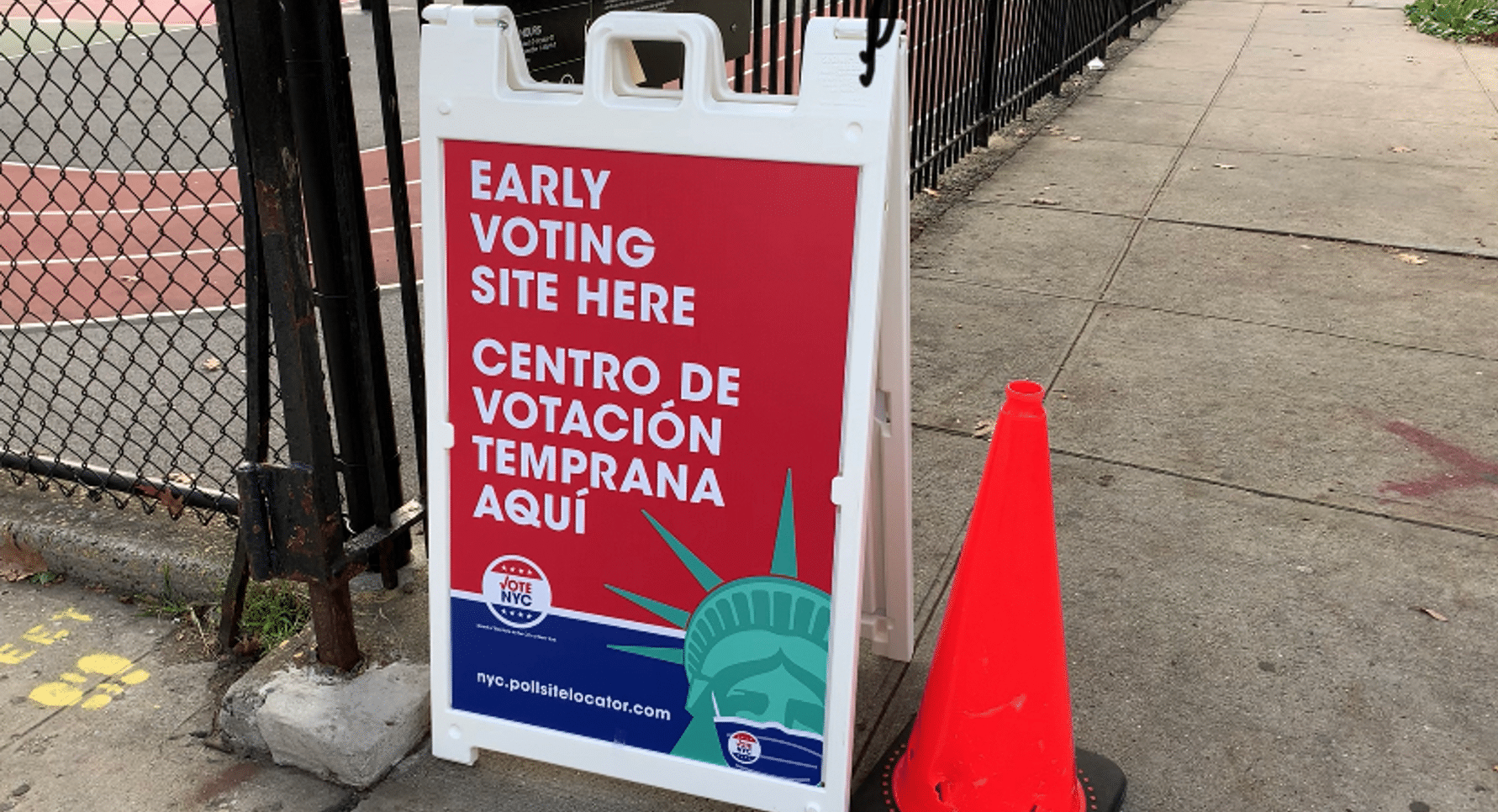

If you came to vote early at Bronx Regional High School, you might have seen me at the door, checking in voters on an iPad or helping others through the affidavit process. I worked for the New York City Board of Elections (BOE) during the nine days of early voting. It was the first time New York had opened up early voting in a presidential race, and I and most of my fellow poll workers tried our best to make voting a good experience. But I also saw first-hand the kind of bungling that the New York Times wrote about recently and attributed to BOE dysfunction and decades of political patronage.

It began before I even stepped into a polling place. Poll workers must complete mandatory training to work election day, but once I finished that I learned I needed another training for early voting. It became a waiting game. I called the BOE twelve times to inquire about my status to work early voting. When someone finally picked up, she asked if I had marked my availability on the poll worker portal. “Yes,” I said, to which she revealed a bureaucratic mystery: the information “for some reason isn’t being received by their office.”

Four days later, a message arrived that I was selected to become a line manager at Bronx Regional High School.

After reading the Times article, I didn’t know what to expect, but I was optimistic that it would be a good experience. I was unsure about the training required for early voting, but there was supposed to be one, and I went to work.

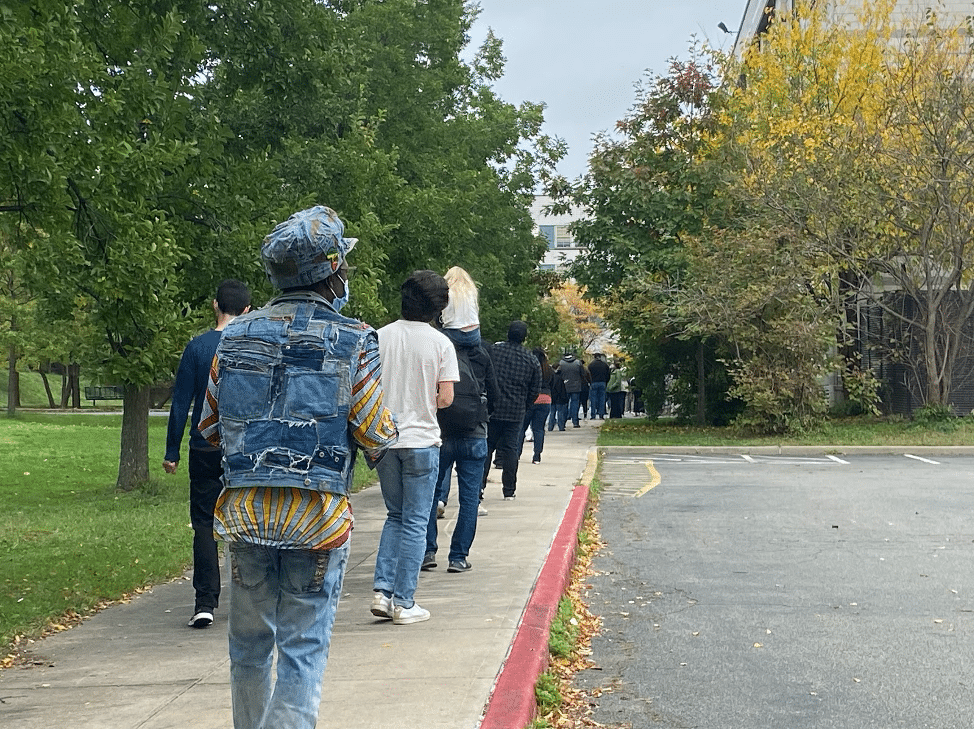

When I got to the high school, the line outside stretched down the street and around the block. Inside, poll workers were busy setting up Ballot Marking Devices (BMD) and tables. Nobody told me where to go or what to do, so I decided to try managing the waiting line. I asked voters if they were at the right polling place. Many weren’t, and I tried to help them find out where they should go.

An hour and a half later, when I went back inside, a supervisor asked where I had been. I explained that I didn’t want voters to wait in line to end up in the wrong polling site. “You are doing too much,” he said, adding that I was too nice.

The line dwindled and I began to fill in for people who went to lunch. One of the people I substituted for took long breaks and napped on the floor. The supervisor just left her there to sleep. She did the same thing every day all through early voting.

It turned out she had a reputation. Someone who had worked a polling site with her previously said, “She does this every time. Everyone sees how she acts and does nothing.” Another said, “She’s not tired, she’s just high off her asthma inhaler.”

The workers didn’t want me to use their names. But a third person explained this was a pattern: “She would come to work late every day and whenever she arrived, she normally just sat to the side and slept. She would even sleep in full view of where voters could see her. And any time she wasn’t asleep, she would get in the way of poll workers who had been working diligently since the opening of the polls. This often resulted in heated exchanges.”

Public naps and long breaks were just the beginning.

I also saw some of the same people complaining about this worker taking long breaks of their own and leaving early before the polling site closed. When workers were asked by the coordinator to fill in, many refused. Several told me they weren’t paid enough to do someone else’s job and again called me too nice because I took the initiative.

The coordinator saw I was eager to learn and placed me at the affidavit and BMD table. Affidavits are essentially paper ballots for voters who weren’t found in the BOE database or were at the wrong polling site. BMD is an electronic device to help blind and vision impaired voters mark their ballots.

The first time a BOE official visited the site, the napping poll worker was snoring at the coordinators’ table by the entrance. The official saw her and said nothing. After the official left, the woman got up, folded her jacket into a mattress and her scarf into a pillow and laid down between two soda machines.

The two coordinators grew frustrated when more BOE officials and poll watchers came to check on the site but ignored her behavior for all nine days of early voting.

Poll workers often argued in front of voters. We used iPads to check voters’ names in the registration rolls. When one worker told another that eating near the iPad was prohibited, the second one got up and yelled while voters waited in line.

On Election Day, I was assigned to the Williamsbridge School with my sister, also a poll worker. We arrived at 5:45 a.m. Voters were already lined up, and I was asked to begin putting up accessibility signs. At 6:00 a.m. the workers were not ready to open the site. Voters became anxious and impatient. “This is ridiculous,” said one. “I won’t make it to work,” another worried.

We opened the doors at 6:15 a.m., and I helped voters find their election and assembly districts. When I told one voter that he was in the wrong polling place, he insisted on voting at this site, so I let him know that he could either go to his correct voting site or vote where we were by affidavit ballot.

A coordinator came over and yelled at me for helping the man. “What are you doing? We don’t advertise affidavits. What’s your role? You need to stay in your lane,” she said. I explained the situation, and she told me that I shouldn’t give suggestions to voters.

She told me to send voters with questions to the information table. But the site only had one information clerk, who also served as the only interpreter. Voters kept asking me questions, and I continued to answer them. Around 9:00 a.m. the coordinator threatened to report me to the BOE for answering questions because, she said, “You violated your role as a line manager.”

Throughout the day few precautions were taken against the coronavirus. There was no social distancing. Masks, gloves, and hand sanitizer were not made available to the workers. We had to provide our own.

Another coordinator who sat at the information table allowed many voters to drop their absentee ballots into the designated box unsealed or unsigned, which left those ballots at risk for being rejected.

Aside from questionable behavior, there were other problems on Election Day. The only ballot marking device for blind and sight disabled voters was broken all day.

Supervisors continued to yell at workers and voters. The woman who scolded me became impatient with a first-time voter who was at the wrong site and asked if she could still vote. She was given an affidavit and then told inspectors she messed up because she was slightly blind. So, she was given another ballot. The angry supervisor approached the table and yelled at her for messing up the ballot. The voter became upset and said she didn’t want to vote. Another poll worker calmed her down, and she went back to the privacy booth to fill in the ballot.

One of my colleagues that day, Erica Ortiz, echoed my thoughts when she said, “The Board needs to do better. Poll workers were mean, lazy, and unprofessional. There is no justification or tolerance for poll workers yelling at voters and egregiously calling them stupid.”

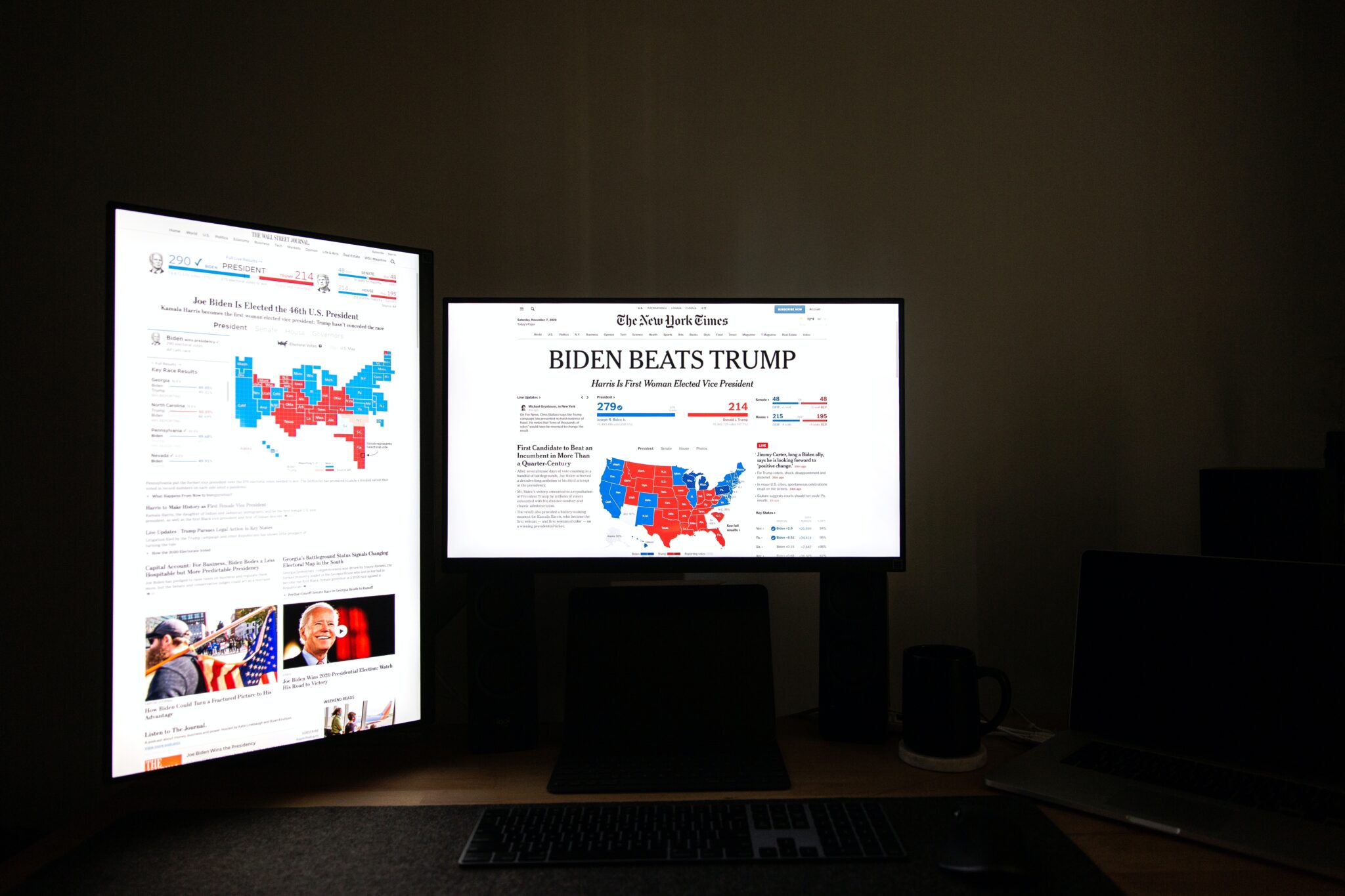

Series: Election 2020