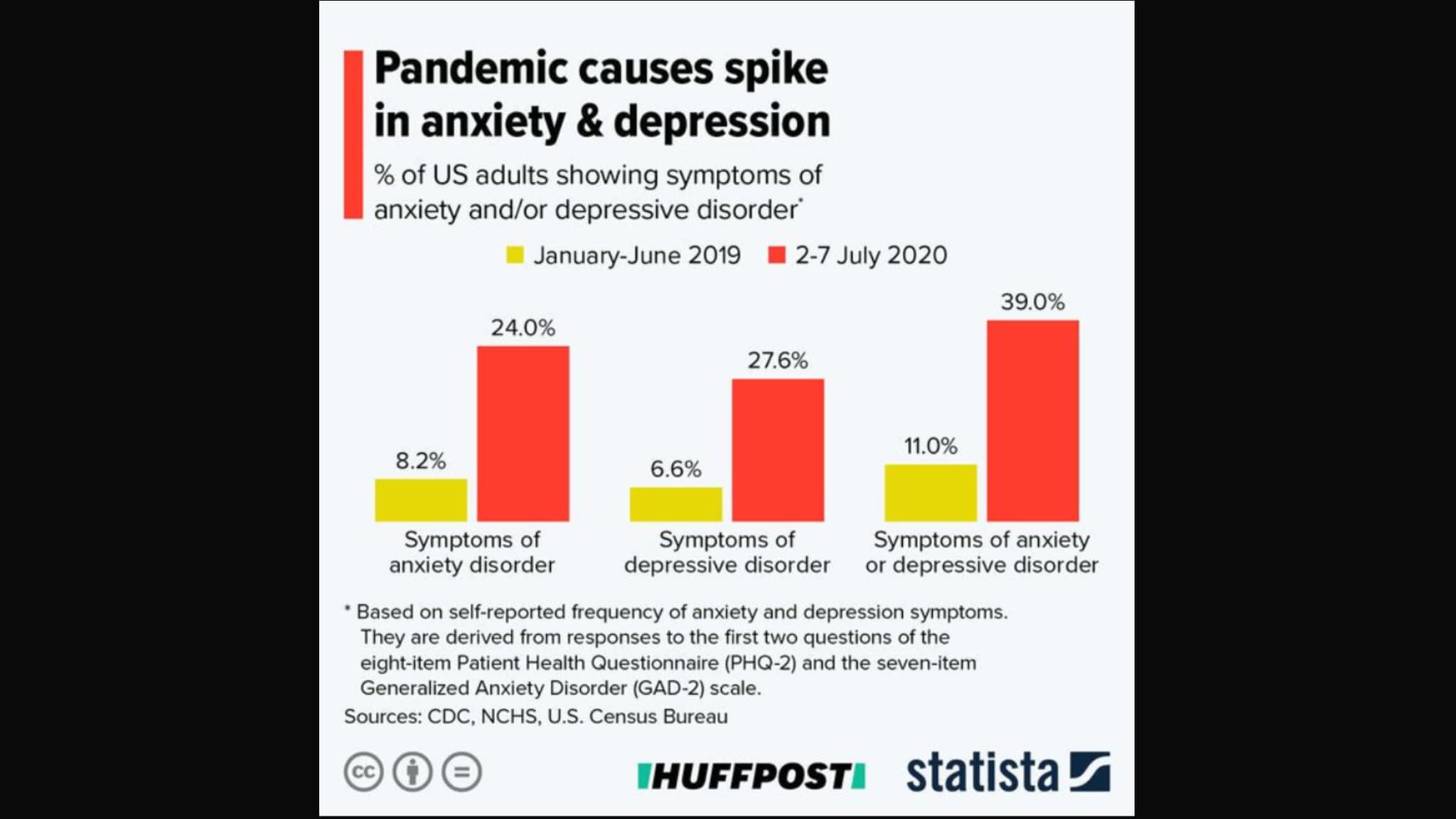

The COVID-19 lockdown was particularly challenging for young adults already struggling with mental health issues. Graphic by Statista/Huffington Post. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Border added for size adjustment.

Maurice Jones suffered from depression and addiction before the pandemic. He started smoking marijuana when he was thirteen, which led to heavier drugs. “I was socially using before COVID, like a party or something. I wasn’t using to cope like I was during the pandemic,” he said. When the lockdown went into effect in New Jersey in 2020, 21-year old Maurice started getting high on ketamine every other day. Maurice was willing to share his story with us but asked us not to use his real name. “I want people to know what can happen, but I’d like to be private about it.”

Maurice ignored his friends and job like they were the virus. Researchers found that many young people across the U.S. experienced serious psychological problems triggered by the pandemic. The Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) found that young people aged 18 to 24 were more likely to report symptoms of anxiety and depression than older people. Maurice described his isolation as a “slow-burning mental prison” where he was his own warden.

Amanda Burke, a Hunter College student in her third year, reported similar feelings during the lockdown. Like Maurice, she asked us not to use her real name. She had suicidal thoughts long before the pandemic and struggled with BPD (Bipolar Disorder) since she was fourteen, “I was on all sorts of mood stabilizers to anti-depressants. Prozac, Klonopin, Xanax—it was so much at once,” she said. It wasn’t until Amanda recovered from trying to take her own life at eighteen that she understood the severity of her diagnosis. “The pandemic reminded me of why I tried to take my life in the first place … It wasn’t so much about the virus. I was never afraid of getting sick, but I was afraid of losing people.”

Isolation hurt Maurice and Amanda, yet their thoughts and feelings are shared by many people in the U.S. in the past year. The CDC found in June 2020 that adults surveyed who were 18-24 years old had seriously considered suicide in a 30-day period at a much higher rate during the pandemic. Feelings of suicide were higher amongst individuals like Maurice who live alone and make it paycheck to paycheck. Amanda does not suffer from the financial problems of Maurice, but she said she felt a similar sense of worthlessness and self-loathing during the lockdown.

At the time of the lockdown, Maurice lived in a Woodbridge, New Jersey apartment. “I had been away from my family for such a long time that it seemed normal to me at the start of the pandemic. It was more about being cut off from the world as time went on.” During his isolation, he became addicted to ketamine. “It was a distraction at first … It would keep my mind occupied for 15-20 minutes, and I would forget about everything in the world because I was just high … but when I came back down it was back to the bleak reality.” Maurice said he was able to get sober for a week prior to getting vaccinated, “I’m 12 days clean, and I’m still going. It’s hard when you don’t have proper healthcare. But I still try,” he said. An uncle came to New Jersey from North Carolina to live with Maurice and help him get sober. With his uncle, Maurice was able to prioritize his money toward rent and basic utilities instead of buying drugs. Addiction runs in Maurice’s family, from his father’s side. This made it easier for his uncle to help Maurice deal with his withdrawal symptoms. Maurice recalls the physical symptoms of shivers and fatigue as the harder ones to cope with. “Without my uncle, I was not making it through that,” he explained.

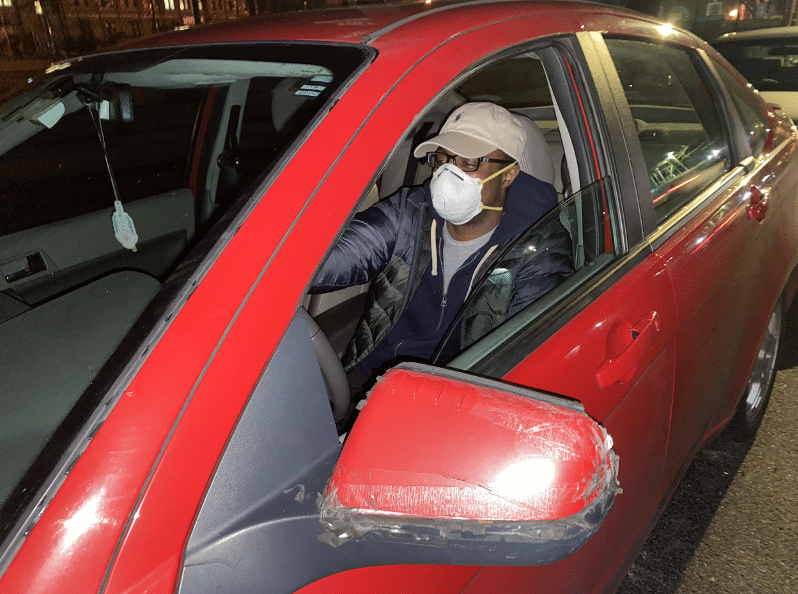

Maurice said that he felt embarrassed about being “babied,” but deep down he accepted that he needed help. He went to work at his local Wawa convenience store, pumping gas on the overnight shift. The location was isolated and quiet most of the time, giving him much time to think. Maurice stated that he understood the importance of sleep while working overnights—something he didn’t understand when he was using drugs. “I would drink coffee to stay awake through the shift, but I didn’t miss my sleep when I got home,” he said. The hours were long, but the work was simple, and by his second week of working, Maurice’s physical withdrawal symptoms had cleared. He feels optimistic. “Addiction is really hard for some of us. I get an itch every now and then, but it’s easy to remind myself I have no reason to use again. There are more opportunities for me now,” he said.

Amanda’s outlook on life changed when her roommate got a kitten named Moonie. When she petted the cat, she felt a good boost of serotonin, the hormone that makes people happy. “I can look at her and forget about how bad my day may have been,” she said. Amanda is still ambitious yet aware of how easy it is to fall back into despair. She wants to earn a degree in early childhood education. “On my bad days, Moonie is a big help. But I also recognize days when I’m not okay. Being aware of that is a powerful thing for the mind.”

Tags: addiction anxiety CCNY Journalism CDC City College Journalism Coronavirus COVID-19 DIARIES depression drugs health Kaiser Family Foundation lockdown marijuana Mental Health pandemic personal story recovery

Series: Coronavirus