The pandemic has made many older New Yorkers more isolated and unable to access needed services and support. Photo by Sanofi Pasteur on Flickr.

“This virus, like for many, has turned my life upside down. I am 76 years old and I was diagnosed with the coronavirus back in May. I was terrified because I thought that I was going to die. I really did,” Albert Rashid said as he fought through his tears. The coronavirus survivor lost his partner a few years ago and he does not have any close people in his life.

Mr. Rashid’s story reflects the problem of many New York City senior citizens. New York City is home to more than 1.7 million people age 60 and over, an all-time high. This includes more than 141,000 residents who are over the age of 85, more than 136,000 who are homebound, and one in five who are living below the federal poverty line, the Center for an Urban Future said in an April 2020 report.

Like Mr. Rashid, many senior citizens in the LGBTQIA+ community do not have children. And some of these LGBTQIA+ seniors who enter nursing homes have to go back into the closet because they fear harassment by fellow residents and staff.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that “loneliness and social isolation in older adults are serious public health risks affecting a significant number of people in the United States and putting them at risk for dementia and other serious medical conditions.”

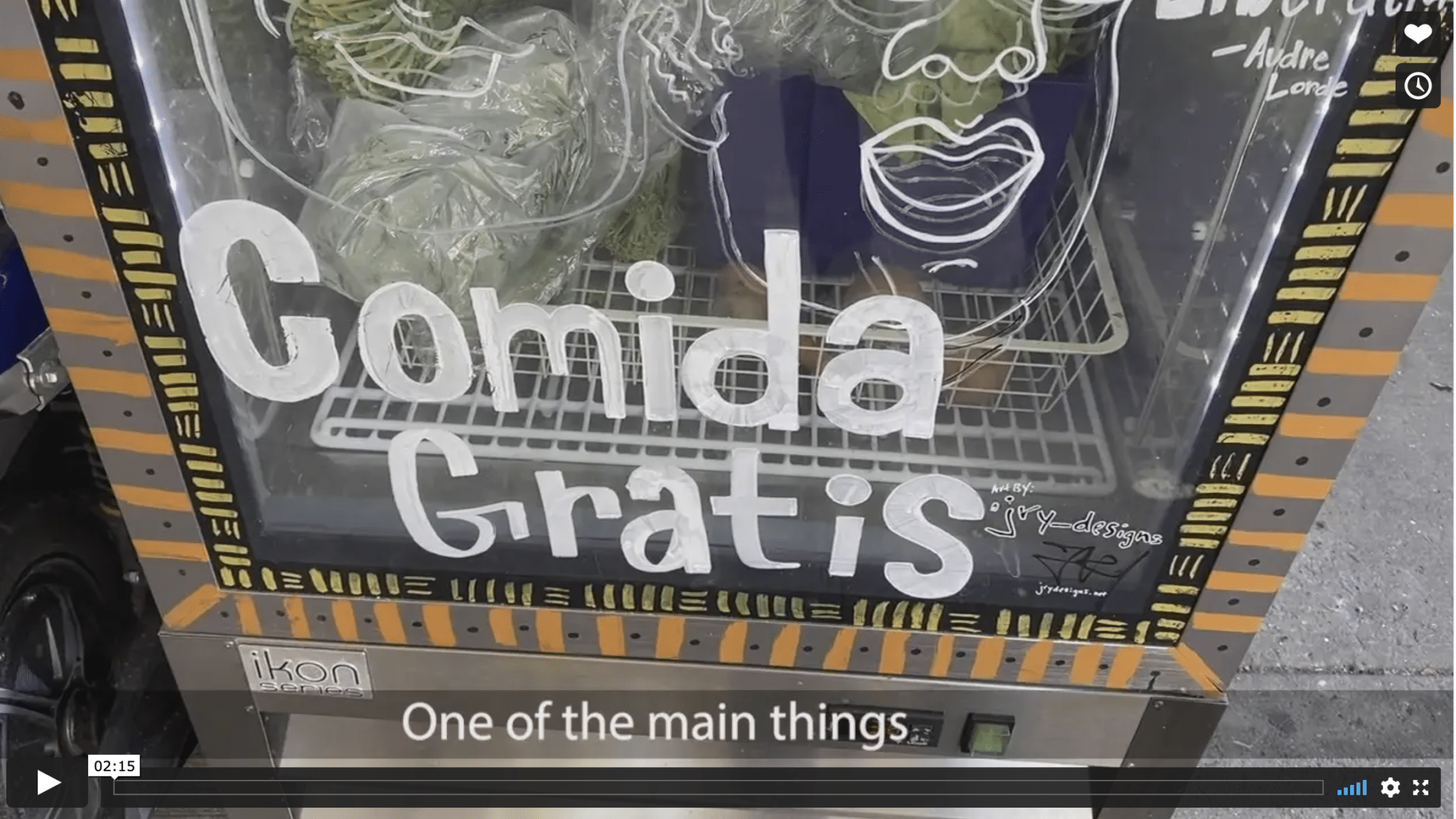

The Center for an Urban Future asked City Meals on Wheels, United Neighborhood House, BronxWorks and other not-for-profits how to help elderly people and reduce isolation during the pandemic. They recommended staffing phone banks to call the older regularly, using senior centers and community kitchens as food banks, and providing no-interest loans to organizations that help older people.

Lorraine Cortes-Vazquez, the Commissioner for NYC Department for Aging (DFTA), is determined to help the elderly. On DFTA’s website, Cortes-Vazquez states that DFTA’s “mission is to eliminate ageism and ensure the dignity and quality of life of diverse older adults. We also work to support caregivers through service, advocacy, and education.”

Cortes-Vazquez continues to work to get the word out to the elderly. The DFTA said in a statement to the New York Post, that “While we have seen an increase in demand for services, DFTA’s case-management program is continuing to take on new clients. Everyone who calls to receive case-management services receives an intake over the phone and is connected to available services, and those with more urgent needs receive a full assessment.”

After being informed about the DFTA services, Mr. Rashid said that he wants to make some changes in his life. He said that he knew about the agency but wasn’t fully aware of what programs it had to offer. “I am 76 years old, but I want to live as long as I can with the best quality of life. I don’t want to be alone anymore, and even though we are in a pandemic, I still don’t have to be.”

Series: Coronavirus