Young people feel overwhelmed and a sense of loss with changes brought by COVID-19. Photo by Volkan Olmez on Unsplash

The coronavirus taught me something about myself. Staying at home, isolating, I realized that I did not live entirely at my home. The new normal for me began when Governor Andrew Cuomo shut down all colleges and schools. I stopped going to The City College of New York.

A few days later my father joined me. He cooks at a Japanese restaurant preparing soba, buckwheat noodles, and it closed when all New York City restaurants went to delivery or take-out only. A week later, my mother requested a week off from her job as a nanny to a baby whose parents are divorced. She would care for the child in New York with the mother during the week and with the father in New Jersey on weekends when she also worked as a housekeeper. But she worried about traveling as COVID-19 cases continued to grow in the city.

When we were in the house together all day long, I realized what I’ve lost.

Friends and other students I’ve reached out to talk about the same feeling of loss and anxiety. We miss the people that we used to be. And we worry because we do not know what the future will look like for us.

This is the longest time my family has spent with one another. Before the coronavirus, we did not share the weekday schedule. My father worked late and woke up late. When he woke up my mother and I had already left. I work Saturdays and when I was at home on Sundays, both my parents were at work. When my father took his day off on Monday, I was out all day occupied by class and work.

Our busy days helped me mask the fact that I did not have my own space at home. I created my private space outside. I studied at CUNY libraries. I went to therapy once a week to talk, and I cleaned the house when no one was home. These were times when I was truly alone. Nobody was encroaching on my space.

In our apartment, my room is the living room. My parents are considerate and leave me alone when I ask, but I am still aware of how small and non-existent my room is. The living room is also a hallway connecting my parents’ room to the kitchen. I can overhear every conversation my parents have. When they call family and friends, I can’t avoid hearing what they say. I can’t really shut them out. Hearing all this talk, I can’t possibly forget that I am not alone.

My friend Gabriel Morales feels an encroachment on his identity as a transgender man. At his college, City College of Technology, he says he felt that he could exist in peace. But when he came out to his mother as a gay transgender man a few months ago, she did not accept it. She continues to use his birth name and refers to him with the wrong pronouns. “When I wear a dress in the house, she will compliment me saying that I look nice. She is not complimenting me as a guy not caring about gender roles, she is complimenting me because she sees it as me ‘accepting’ my assigned gender,” he told me. “Even though I know putting my name on the CUNYfirst account was unofficial, it was nice to see my name and hear people [in his classes] refer to me by my name.” When he was outside, he was a stranger. Nobody would intentionally confront him about his gender.

Ita Flores, another friend, feels anxious constantly. Isolating did not change her routine a lot because she is always surrounded by family. She waitresses at Casa Coriz, the restaurant her family owns in Glendale, Queens, and babysits for her sister. Her anxiety comes not from an increase in family time. It comes from wondering about the future and the aftermath of this virus.

She and her sister have asthma, and she worries about what would happen if they contracted the virus. “I am growing up faster, and things I thought I would confront when I was older, I have to think of now,” she said. “Like I need to learn more about student loans because somehow I still owe money to City Tech. I need to learn about small business loans because we need to apply for one. And when I eat, I worry about groceries.” Like me, she worries about the future. “Even when this is all over,” she told me, “I’ll have to deal with everything that was in suspension — school, the restaurant, money.”

Judson A. Brewer, a psychiatrist and an associate professor at Brown University, advises people to break the anxiety cycle. In his New York Times article, he urged people to notice when we are panicking or getting anxious and what happens because of it. He writes, “Just by taking a moment to pause and ask the question, we give our prefrontal cortex a chance to come back online and do what it does best: think.”

My friends and I have been trying to use his advice to contemplate what we lost and the different ways we can recreate those instances. Although the pandemic has created sudden problems, we can also understand that we still have some control.

I try to do whatever I can to create a space for myself. I cannot create a physical sense of space, so I try to create it mentally. If my parents call somebody when I’m in a class or study session, I drown them out with my headphones. I also try to use the English language as a barrier. They are fluent in Nepali but have a hard time understanding English. This creates my own safe space. My parents do not understand me when I speak English, but my friends do and I can be vulnerable with them. I now comfortably call my therapist on the phone. I feel safe talking to her in English.

The coronavirus crisis gave Gabriel time to paint, write in his journal, cook and embroider. He has found solace and opportunities to practice and learn skills through these creative pursuits.

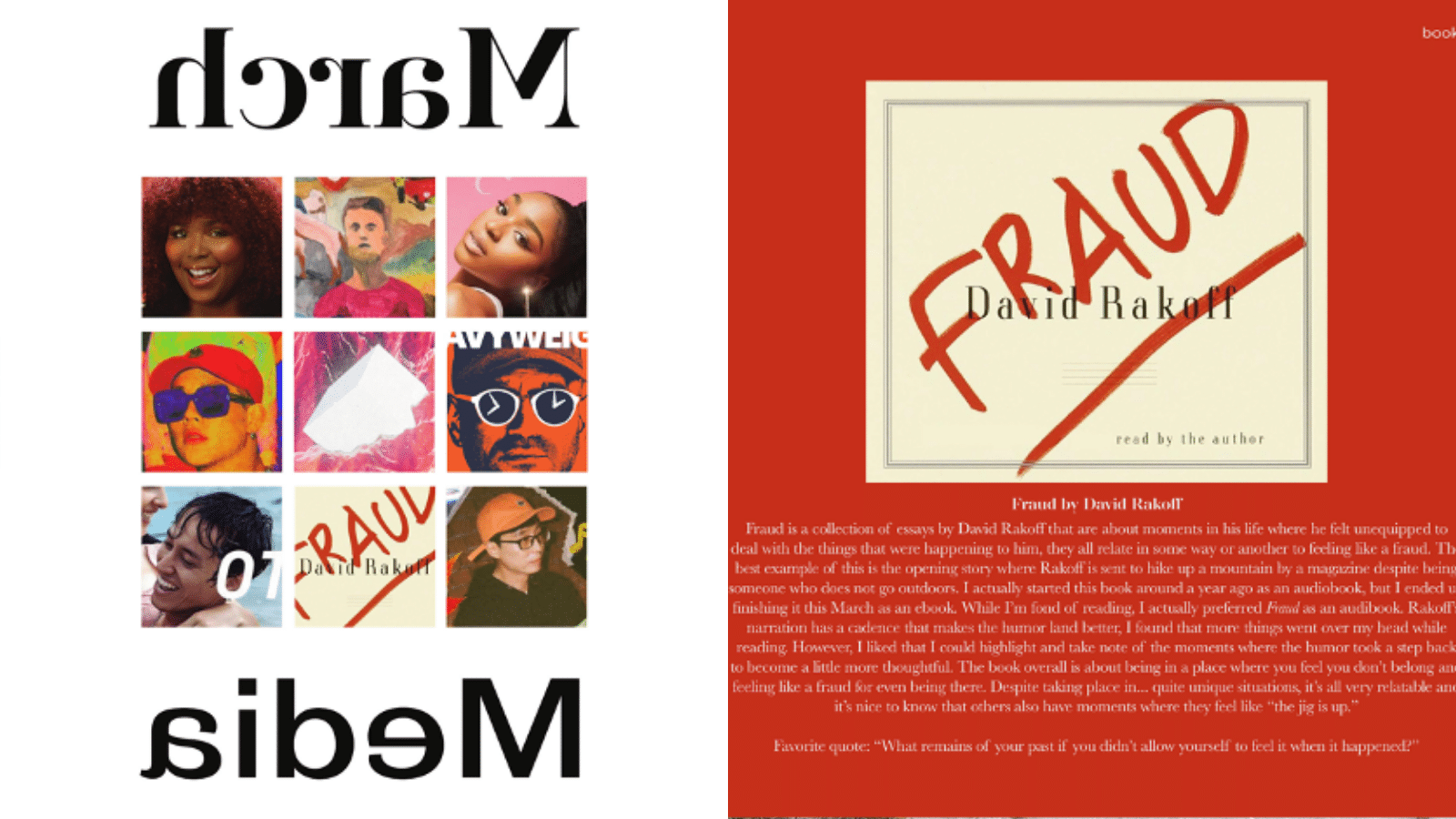

Ita makes the use of her time by trying things she never had the time to try before. She was always preoccupied with her family, their restaurant, or schoolwork before. She texted me to say, “Usually it feels like there’s a never-ending task list that’s impossible to accomplish, but I’ve been able to enjoy things more with the knowledge that there’s nothing left to do because everything is shut down.” She finds comfort in the absence of that task list and is trying to let her artistic side grow. Ita publishes an online journal where she reviews music, podcasts, books, films and shows. She explained in her editor’s letter how, after isolating in her apartment, she filled her recent journal with “better things,” looking for “escapism or self-care” in light of a “growing awareness that the kids are not in fact alright.”

We cannot control how this virus spreads and what it takes from us, but we can control our reaction to it.

First published April 26, 2020.

Tags: CCNY Journalism Coronavirus COVID-19 Cuny Mental Health New York State on Pause Sajina Shrestha

Series: Coronavirus