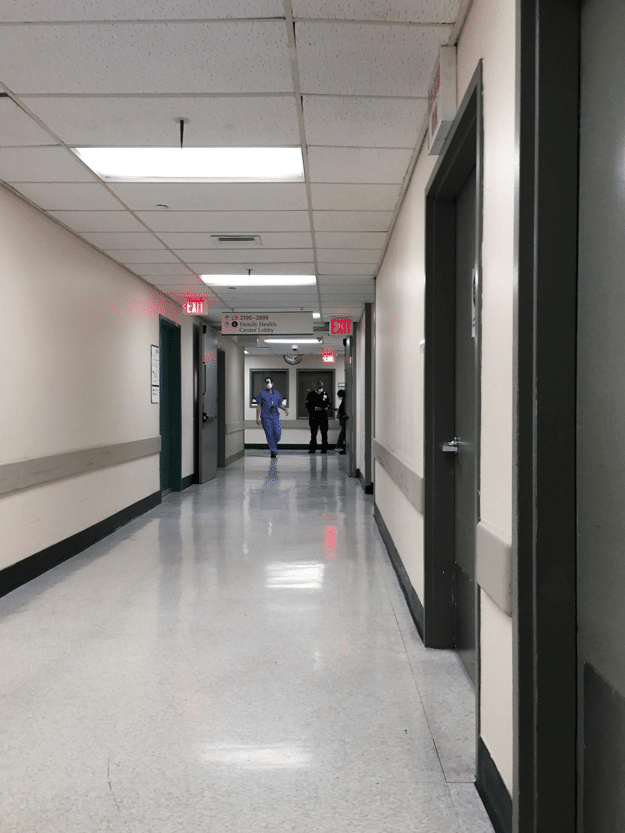

The dreaded corridor leading to the emergency room

Since the coronavirus struck, I woke up every day to listen to Governor Andrew Cuomo’s press conferences. I worried, but I thought I was safe. Then I fell down the stairs and faced my worst fear. I had to go to the hospital.

I was living with my girlfriend, Flora, at her mom’s house in Bay Ridge. I moved there after I had to leave my dormitory at The City College of New York in Harlem because the state planned to house members of the National Guard there. My family, originally from Hawaii, lives in Virginia, and going home wasn’t an option.

That morning I pulled on my socks and started downstairs. My heel slipped on the smooth wood and flew out from under me. I fell to the bottom of the staircase as my back slammed against the steps. A stabbing pain took my breath away. It hurt so much I couldn’t move my arms. I was still trying to catch my breath when Flora found me. She helped me limp back up the stairs, trying to keep my back straight. I lowered myself onto my bed, and that’s when I began to worry about coronavirus.

Like other New Yorkers, I watched COVID-19 cases rise exponentially but I tried to stay safe. I only went out for groceries and exercise. I washed my hands thoroughly and followed all other safety precautions. I’m alright, I thought to myself. Until now. The fear of what could happen mixed with my pain made me panic. “I don’t want to go to the hospital,” I thought. “I need to be okay.”

My breathing was so heavy that I could barely talk, and my head felt like everything was spinning.

I told Flora, “I don’t need to go to the hospital.” My breathing was so heavy that I could barely talk, and my head felt like everything was spinning. How am I ever going to make it through this pain? I thought.

Flora’s voice broke into my confusion. “Yes…he fell down the stairs…nineteen…male.” She was talking to 911. Maybe five minutes passed. The outside door creaked. Flora said, “He’s up there.” Heavy boots stomped up the steps that I had fallen on, and two young men, EMTs, came into the room. They wore navy blue medical jumpsuits, clear, see-through glasses, blue surgical masks and purple gloves. They approached me cautiously and asked me what happened before they touched me. “Do you have a fever or cough?” one asked. They seemed afraid, and I was afraid to have them touch me.

After I said I didn’t have a cough or fever, they lifted me up and put a brace on my neck. I sat on the edge of the bed while they took my pulse and blood pressure. They felt around my back and asked me to explain where it hurt. One said, “You should go to the hospital. You might have injured your spine.”

My heart started to race even harder because I didn’t want to go to the hospital. I didn’t want to be anywhere near COVID-19 patients. But I said nothing. They carried me down the stairs and lifted me into the ambulance. One of the EMTs gave me a surgical mask and a pair of rubber gloves. “Take another pair just in case you touch anything,” he said.

“This is it. I’m going to catch the virus.”

“Would I come in contact with anything that had the virus on it? Did they clean enough?” I wondered. And then, “This is it. I’m going to catch the virus.”

The ambulance pulled up to NYU Langone Hospital, and they pulled me out of the ambulance and put me into a wheelchair. Once we got into the hospital, a nurse approached and asked the EMTs, “Does he have a cough or a fever?” Even though they told her no she said, “I’m going to check him anyway.” She took my temperature and she saw that I didn’t have a fever and disappeared. I sat in a crowded waiting area. Doctors and nurses seemed to run past me in a blur. An older woman lay in a bed about ten feet from me and I wondered, “Does she have COVID?”

A nurse approached and told me to put my feet up on the wheelchair. But I felt foggy and achy and didn’t understand her. She yelled, “I said, ‘Put your feet up.’” Then I got it. She pushed me down a long hallway through the doors into the trauma area. “He needs an interpreter,” she told the nurse at the desk. But the second nurse asked, “Do you speak English?” When she realized I could, she called a doctor over.

I was the only patient in the Trauma Unit, and I began to think about how much this might cost. My parents would have to pay, and I felt bad for them. A young doctor, who seemed like he was fresh out of medical school, examined my back and said, “You’ll need a CAT-scan.” I wondered if I’d have to lie back and if I would come in contact with the virus. But I agreed to get a scan anyway.

A nurse wheeled me into the CAT-scan room. I sat there waiting. Doctors brought in a man who had suffered from a stroke and needed a scan. Still waiting, I became lightheaded. Breathing with the surgical mask made me nauseous. I took off the mask for a moment to catch my breath.

The stroke victim finished with his scan and technicians wiped down the machine thoroughly. But I still worried as attendants pushed me into the doughnut-shaped machine. What if they missed a spot? My scan over, I was wheeled back into the nearly empty trauma unit. I laid down in the hospital bed and waited.

The results were back in no time. The first young doctor I had met walked over to my bed. “Well, good news. No fractures so it’s probably just a bad sprain,” he said. I was relieved.

“They don’t care. As long as you’re not positive with COVID you have to work.”

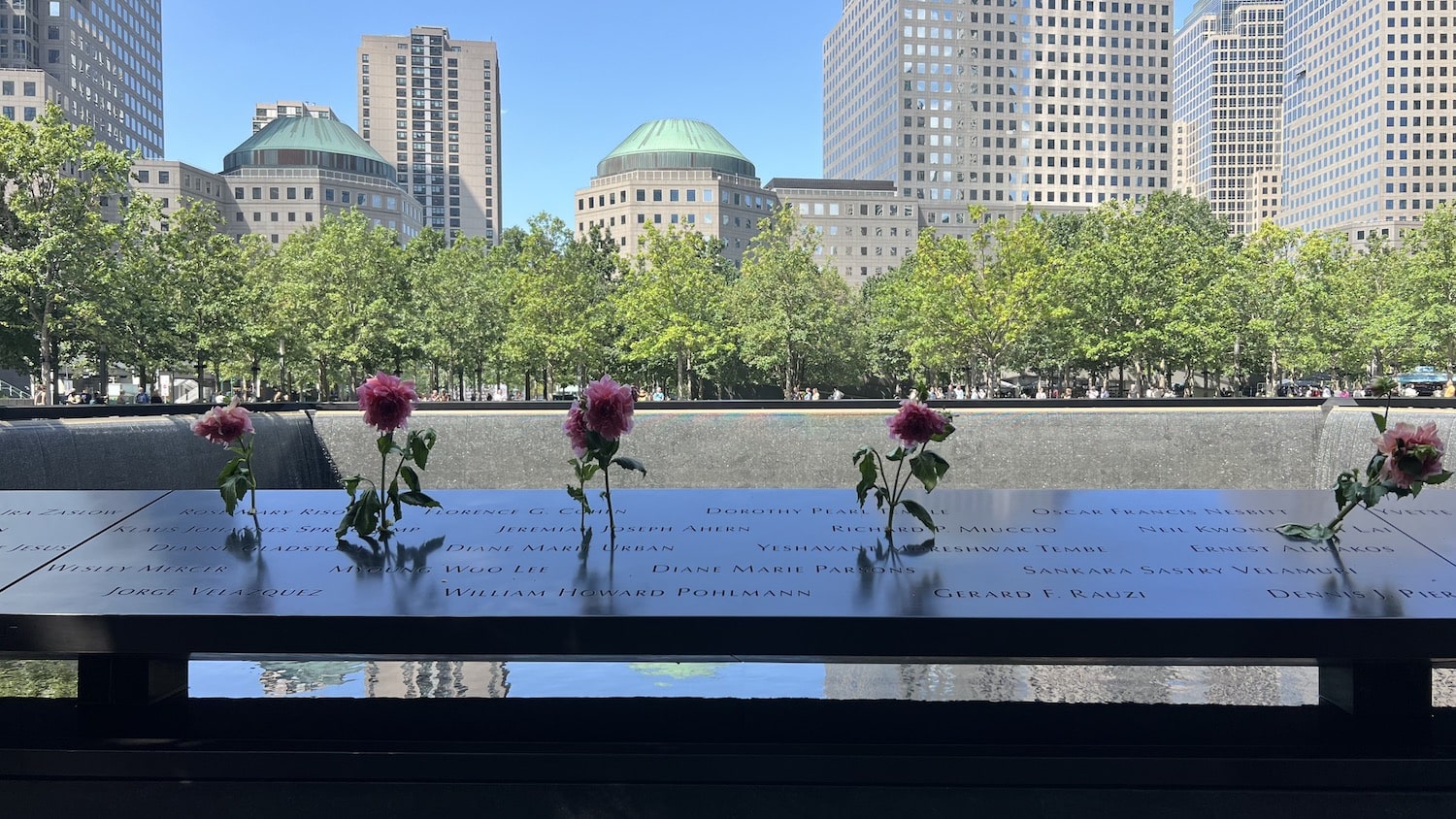

As I lay there waiting to be discharged, I overheard two nurses. One said, “Did you hear about Julie? She called out today.” The other replied, “That poor woman, she was throwing up everywhere yesterday. They don’t care. As long as you’re not positive with COVID you have to work.” Hearing this, I thought about the jobs these healthcare workers do and the hours they’re spending taking care of people, at danger to themselves.

I signed insurance and discharge forms, and I was free to go. Flora and her mom picked me up. I was careful not to touch anything when I entered the car. I washed my hands as soon as I got home, stripped off all of my clothes, put them into the wash and took a hot shower. I was still terrified even though I took all the proper precautions. “What if I have COVID?” I thought.

I was lucky enough to be able to go home and sleep in my own borrowed bed that night. But there were hundreds of thousands that weren’t as lucky.

Tags: CCNY City College Journalism Coronavirus COVID-19 Emergency Room Health Care Workers Kainoa Presbitero

Series: Coronavirus