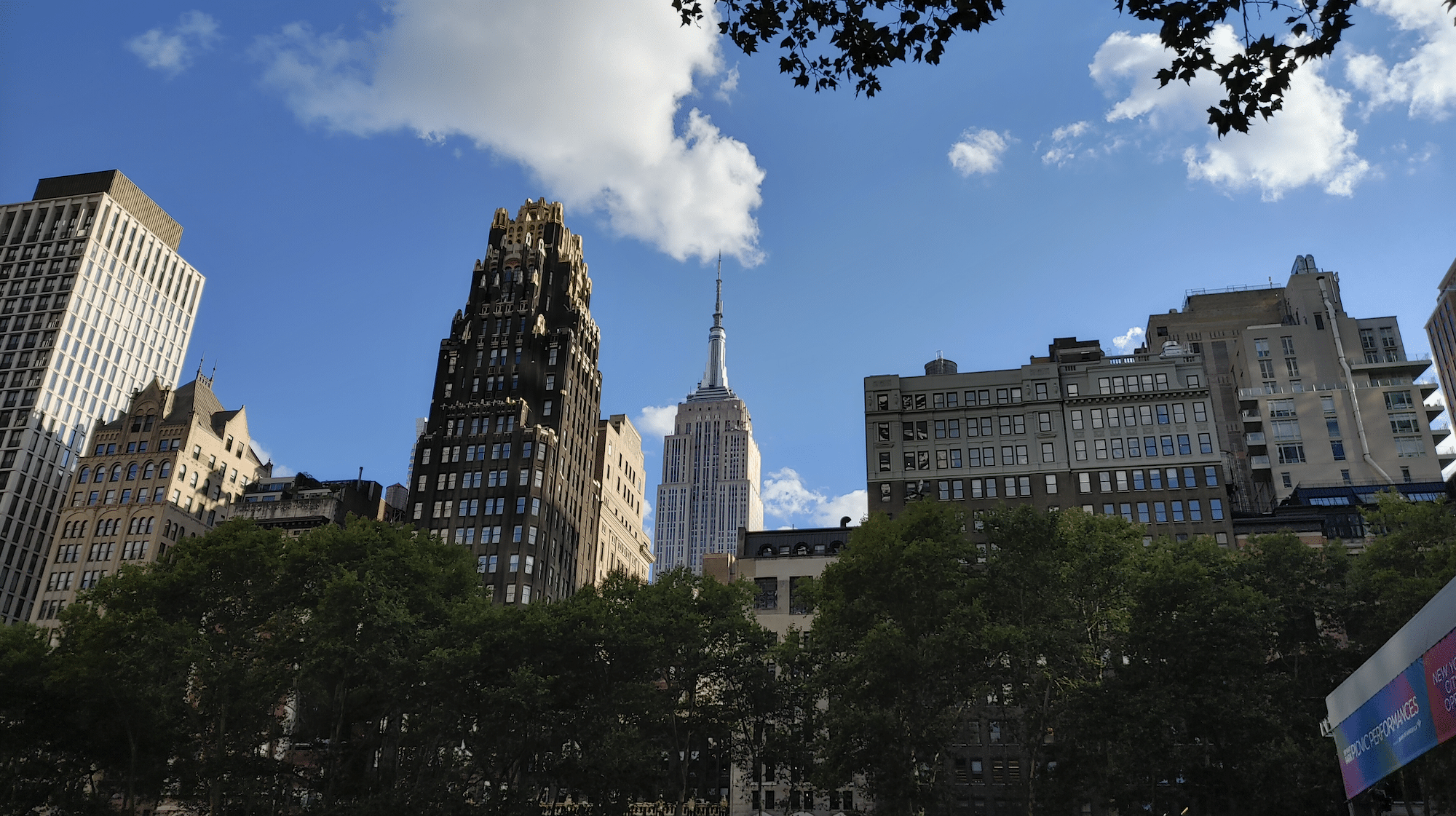

Density and concrete add to the heat in New York City. Photo by Jayden Pantoja.

MANHATTAN, N.Y.

“I remember cancelling some plans I had with friends last summer because it was too hot to be outside,” said Robert Suarez, an East Harlem resident. The 27-year-old Suarez, like others in his neighborhood and densely populated communities like Harlem and the Upper West Side, felt the effects of climate change. “You get tired when you’re out in that heat for so long. So with days like that, it just makes me think that this summer will be the same thing,” he said.

The 2024 summer season was the hottest to date, according to NASA’s Global Summer Temperature Report. In comparison to the summer of 2023, the temperature rose by 2.3 degrees. With warmer weather comes events like coastal storm surges, flooding and that leads to disruption in the delivery of food and other vital services, according to the New York State Climate Impact Study. The spikes in temperature are also dangerous for New Yorkers. The city had 580 heat-related deaths in 2024, and the city’s heat mortality report found that most of those who died lived in homes without air conditioning.

At The City College of New York (CCNY) James Booth, deputy dean of the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, explained that the city experiences a phenomenon known as urban heat island. He said, “The energy of the sun hits concrete in a different way than it hits soil. That’s why it’s hotter in the city than in the suburbs or the country. In a town or untouched forest areas, you have less capacity for holding heat and releasing it during the day because the energy of the sun comes into the plants and the soil and it is able to be transported deeper into the soil. When heat hits concrete pavement, it is not going very far down. It is trapped on the top layer and then that is heating the atmosphere even more.”

In addition to the concrete, we have the problem of greenhouse gas emissions. The EPA’s Global Emissions Economic Sector graph shows that 34% of emissions comes from electricity and heat production. We added to global warming with the electricity we use to cool or heat our homes, charge mobile devices, and power computers. Cars, trucks and buses account for emissions, which also heat up city streets contributing to the rise in temperatures.

Scientists and politicians have begun to address the problem. In New York, the Mayor’s Office of Climate Justice (MOCEJ) started funding initiatives like the Environmental Justice NYC (EJNYC) plan, which aims to help low-income families overcome environmental health hazards. But James Booth said the project stalled during COVID. “The city as a whole is facing a budget crisis in part because of shifts in where banking and commerce are setting up. We’re in a place right now where we really need to pay attention to the climate, but our resources are thin,” he said.

There is some money for the Home Energy Assistance Program (HEAP) which aims to provide efficient cooling for homes and lower utility costs. That can help. But it is funded by the federal government and the money could disappear. The Trump administration canceled federal projects and grants to cities and states. That will make it harder for public officials and climate organizations to continue their work and help New Yorkers. Still, scientists and researchers plan to keep working to try to reduce greenhouse gases, help the environment and reduce the drastic climate changes.

Tags: Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences he City College of New York (CCNY) HEAP Home Energy Assistance Program James Booth Jayden Pantoja NASA’s Global Summer Temperature Report

Series: Community