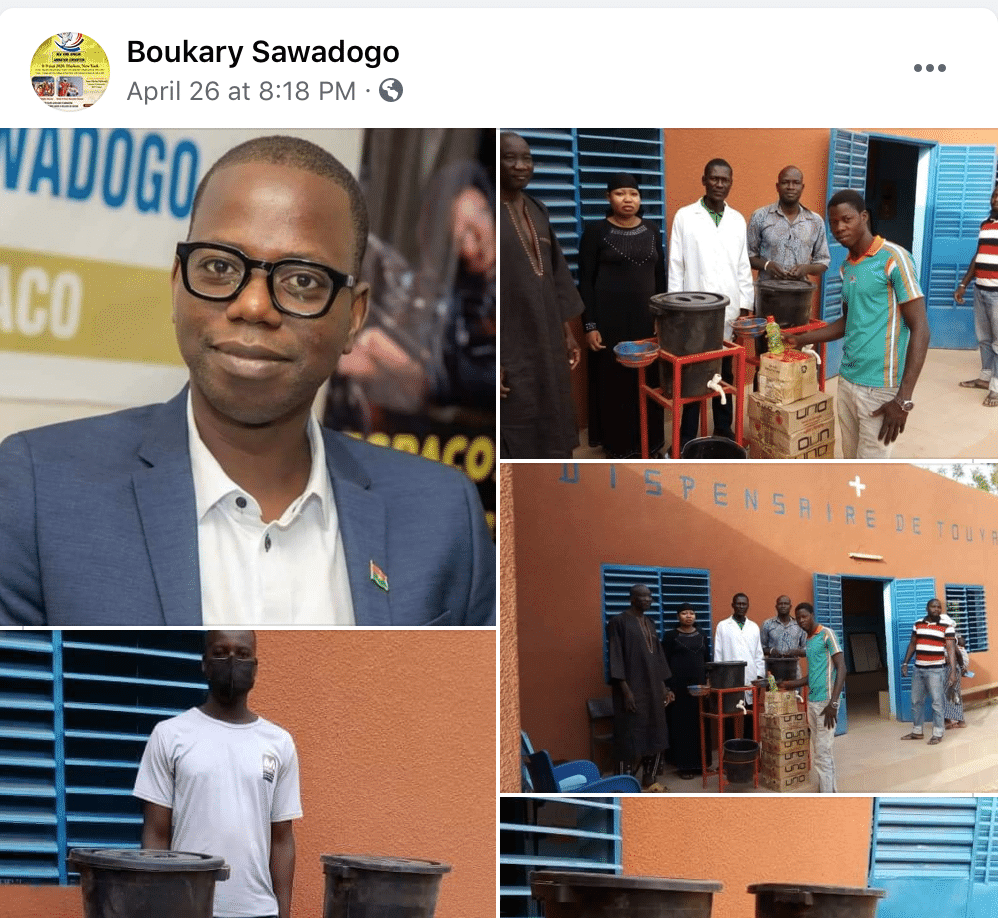

“It’s the community that makes us who we are. With no community we are nothing,” Boukary Sawadogo said. That’s why he has worked to educate and help the African community in New York and people in his native Burkina Faso during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Dr. Sawadogo, a professor at The City College of New York, teaches African cinema, film history and theory. He came to the United States for graduate studies in 2006 and has maintained close ties with fellow African immigrants. When the scope of the pandemic became clear, he had to postpone the book tour for his recently-published West African Screen Media: Comedy TV Series and Transnationalization from Michigan State University Press. The world was locked down.

He looked around and wondered how he could help. He reached out and put on a mask and gloves, bought food and made a delivery to the Association des Burkinabè de New York to distribute in the Bronx and Harlem.

The book that he had just finished writing about Africans in New York made him aware of the need in the immigrant community. He became concerned that people of color suffer from COVID 19 at disproportionately high rates. “Blacks in New York count for 22 percent of the population but in terms of death, they count for almost 30 percent,” Sawadogo said.

Many immigrants and people of color are essential workers and are exposed to the virus. Some health officials say that pre-existing conditions like diabetes and obesity make African Americans susceptible. Sawadogo said these conditions stem from systemic neglect and unemployment or low wages. “These are aggravating factors, which means if you have pre-existing conditions you’re automatically more likely to be a victim. It speaks to something deeper, which is poverty. That’s simple.”

Professor Sawadogo thinks that immigrants, particularly the undocumented, are often afraid to go to hospitals and may not get the help or the information they need. That’s why he began to use his Facebook page and other social media to warn people to stay at home and wear masks if they have to go outside.

But he also looked back at his home country. He was following the news when he noticed that the emphasis in Burkina Faso was on urban areas. Even though The World Bank approved $21 million on April 30th for first aid response and training for 2,000 health workers in Burkina Faso, it seemed the small villages were neglected. Sawadogo didn’t think the aid would get to people who need it the most.

“I am not rich. I am just a college professor with a salary,” Sawadogo said. But he sent aid, food, masks and gloves to his village community health center in Touya in Burkina Faso. The center plays pivotal role in providing essential health care to villagers. He said, “We are more effective helping each other.”

He also sent aid to Ouahigouya, the seat of the province with administrative oversight of Touya. “I made the donation to the mayor’s office to help them provide assistance to the people who had to leave their villages due to jihadist attacks,” he explained. “These internally displaced people find themselves in the city of Ouahigouya with no means to support themselves. And they are even more vulnerable during this coronavirus health and economic crisis.”

A local journalist in Burkina Faso contacted him to write a story. The reporter quoted someone who said, “He did much more than their rich politicians back at home who drive around in large luxurious SUVs.”

Sawadogo laughed off the praise and said, “It’s not about me, but the community.”

Living in Harlem, he saw the growing economic and cultural influence of Africans in the neighborhood. He thinks the increase in the number of West African students at City College reflects what’s happening in his neighborhood and other communities throughout the city and the country. “The population of Sub-Saharan immigrants in the United States has doubled every ten years from 1980s to present. As a result, more students of African immigrant parents are attending college in large cities such as New York. Many students from West Africa transfer to City College from CUNY schools, particularly from BMCC,” he said.

He also points out that COVID-19 changed the western narrative about Africa. “The disease spread to Africa from the West, contrasting with the usual images of the continent in the media being associated with diseases and chaos.” Sawadogo said the virus reveals every country’s vulnerability. “The distance between the global north and south has been blurred in terms of discourse. It is true that the response capabilities to the crisis may differ between wealthy and poor countries, but the spread of the virus between countries is not so far reflective of the world order of superpowers and small players.”

His Facebook posts about the donations and WhatsApp group discussions gained attention. Many people originally from Burkina Faso, who live in Harlem and the Bronx also stepped up to donate money to help those in need in their New York communities.

Sawadogo added, “I am very happy and proud to see that other people are following my lead in helping their communities in this time of crisis. Every one of us has the potential to bring about change, and often the inspiration to act comes from people around us. In this respect, I am proud that my donations were the catalyst that motivated people to help vulnerable community members.”

Tags: Africa Burkina Faso Coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic The City College of New York West African Cinema