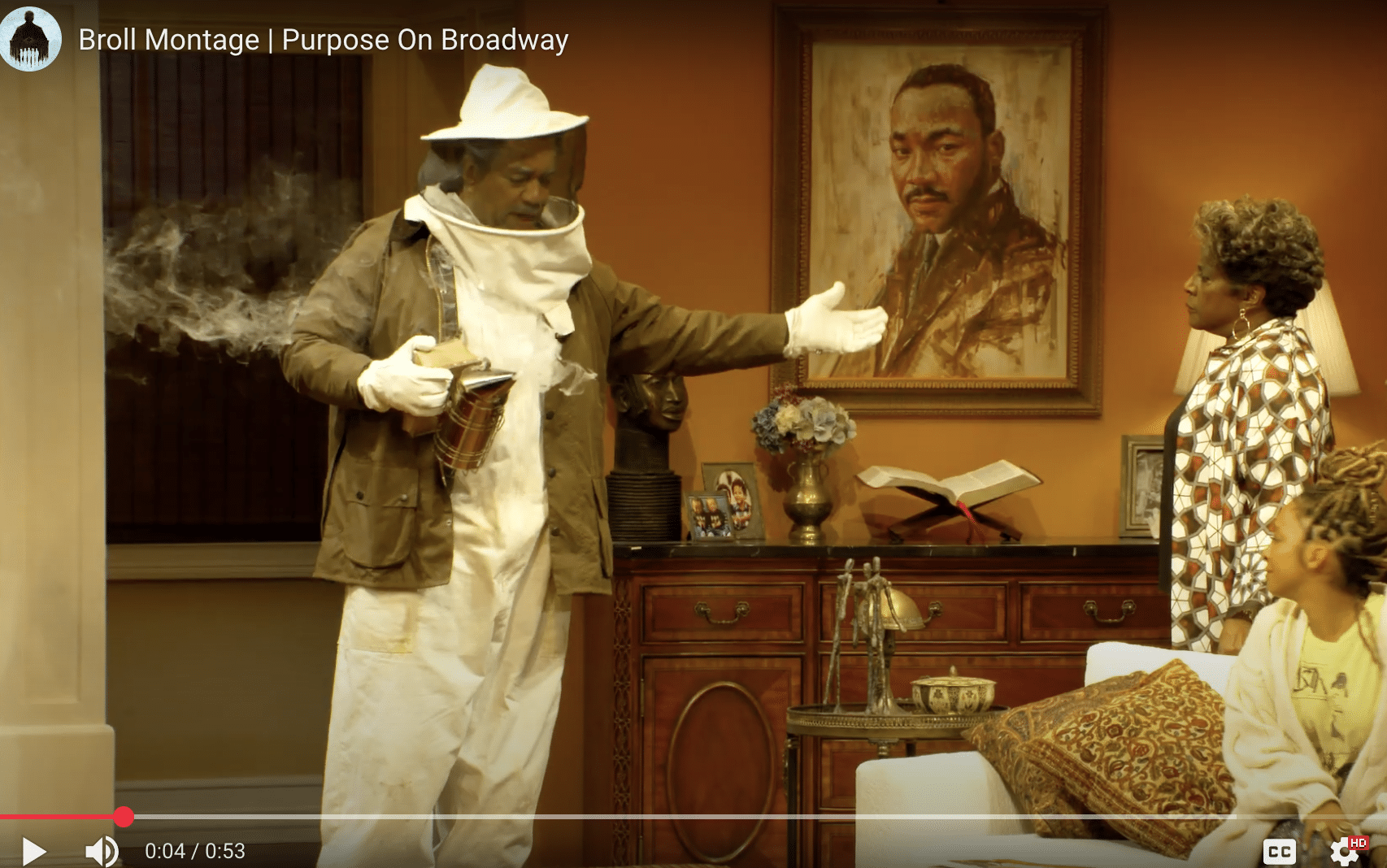

Screen shot from publicity material for Purpose.

Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s Purpose new Broadway play, which opened in March at the Helen Hayes Theater, begins with a fast-paced, engaging exploration of family dynamics. Its sharp wit and deep humor initially makes the play feel like a brilliant sitcom. But as the story unfolds, it shifts gears, revealing a more complex exploration of complicated relationships, hypocrisy, and legacy. Beneath the laughter, Purpose highlights another big issue. The playwright, the director Felicia Rashad and the actors are all Black and that is rare on Broadway. The theater world has pushed for more diversity. But many question whether this is a surface level effort at inclusion.

Actor Shawn G. Elliot acknowledges the impact of increased representation but believes it doesn’t go far enough. “The push for diversity in theater has definitely opened up more opportunities for underrepresented actors,” Elliot said. “But real change takes more than just casting. If there aren’t diverse voices behind the scenes, like in writing, directing, or leadership, it can start to feel a bit performative.” This lack of representation behind the curtain affects not just who gets cast, but whose stories get told and who has the power to tell them. Iconic plays like Porgy and Bess, Spinning into Butter and White Savior about people of color, for example, have been written by white playwrights.

Actor and playwright Jociel Tambone sees this as a missed opportunity to allow communities to tell their own stories. “Some of the most well-known shows featuring people of color weren’t even written by us,” he points out. “If we actually open up the conversation and make theater more accessible, we’ll bring in more people of color not just as actors, but as creators shaping the industry.”

Even before stepping onto the stage, many aspiring artists face challenges simply getting their foot in the door. Theater education is often treated as an extracurricular activity rather than a viable career path, especially in lower-income communities. Tambone reflects on his own experience, saying, “I wasn’t exposed to theater until the 9th grade, and I never had a real conversation about pursuing it professionally. I guarantee you, if you expose kids of color from places like the Bronx and show them that theater isn’t just a hobby, but a real career, the opportunities won’t feel performative.”

This early exposure matters. Without it, young artists of color are at a disadvantage compared to those who grow up with access to theater programs, industry mentorship, and professional training. The lack of resources creates a cycle where only those with privilege make it through the doors.

For those who do pursue theater professionally, the obstacles don’t stop at training. Many actors of color struggle to break into the unionized world of professional theater. The Actors’ Equity Association, which provides essential protections and benefits for stage performers, requires actors to book a paid job before joining. A major hurdle for those without industry connections. “They can do that cute thing with Equity and say, ‘Oh, you can join if you book one paid job,’” Tambone says. “Which is great, but Equity is a whole different beast.”

Even when actors of color and ethnic minorities land roles, they often find themselves cast in ways that reinforce stereotypes rather than expand narratives. Actor Danah Hardison argues that the industry’s approach to diversity still operates within a limited framework. “The push for diversity in casting can create opportunities,” she says, “but it doesn’t address the bigger issue. That people of color are not even thought of in these spaces, nor in the stories being told. It can come across as if we’re an afterthought, or just a tool to reach a wider audience. Essentially, a sell.”

The push for real, structural change in theater has led to initiatives like The Shubert Organization’s Artistic Circle, which aims to develop and fund stories centered on the lived experiences of underrepresented artists in the Black, Indigenous, and People of Color Communities (BIPOC). This program is part of a broader effort to address the growing demand for more inclusive storytelling. Changing audiences may play a part in efforts to develop new talent from previously marginalized communities. The Broadway League reports that 29% of theatergoers are people of color, and Playbill puts the number at 28% for 2024.

But some actors and theater professionals feel like they have waited long enough for theater institutions to change. They have moved forward with their own plans. In July 2020, industry veterans Reggie Van Lee, T. Oliver Reid, and Warren Adams founded the Black Theater Coalition (BTC), a nonprofit entity committed to increasing Black representation in theater by 500 percent by 2030. The BTC’s ambitious goal reflects the growing push to ensure that people of color are not just seen on stage but also empowered to shape the industry as a whole.

“Theater has the power to shape culture,” Elliot says. “But real progress happens when those voices are given the power to shape the industry from the ground up.”