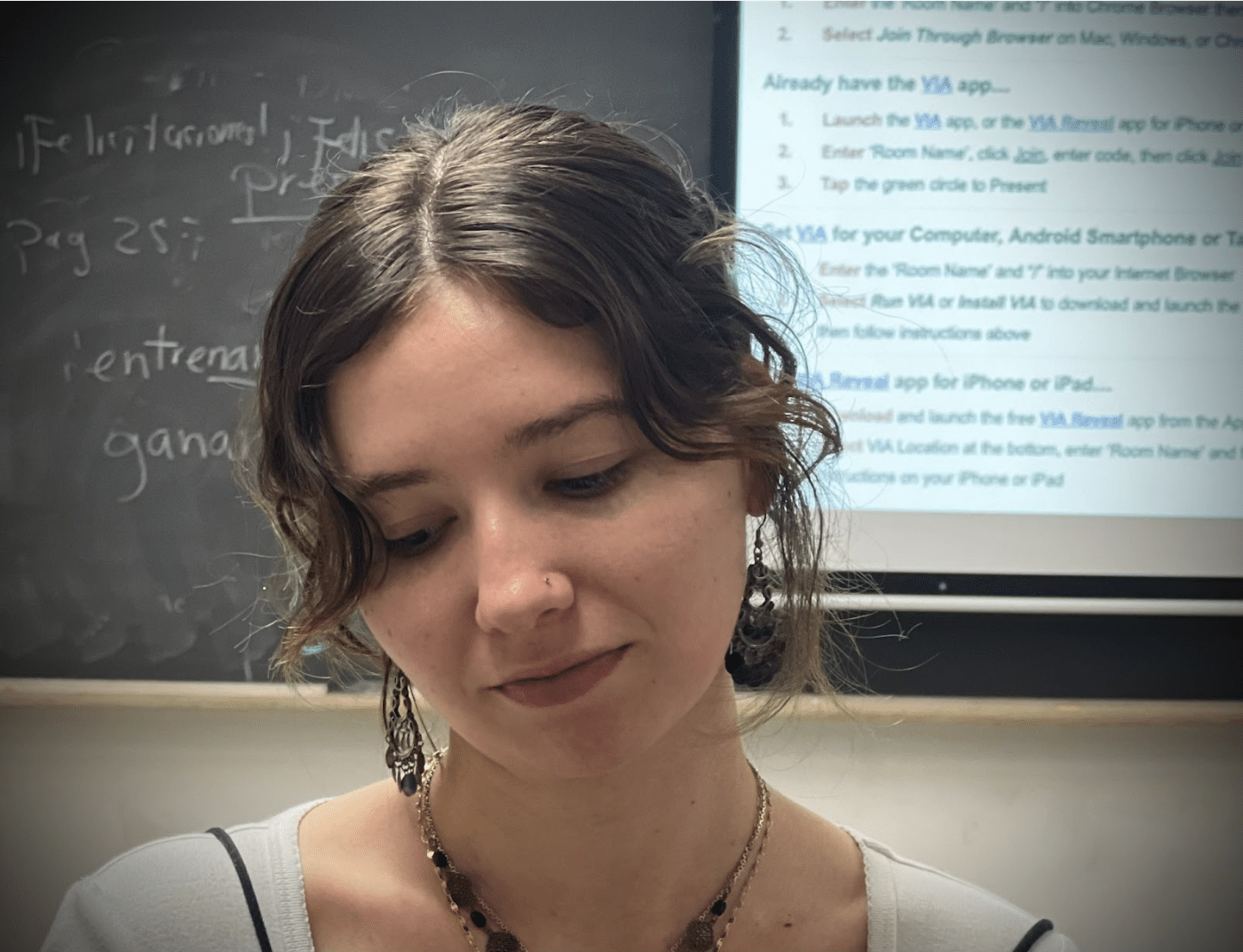

Yvonne Huatin Chow posing for the camera in March 2024. Photo by Cristy Burton.

In 2014, Yvonne Huatin Chow found herself in a crowd of mostly Asian people at the Brooklyn Museum, subconsciously apologizing for her community “taking up too much space” in this event featuring Chinese artist Ai Weiwei. She explains that this moment sent her “on a self-discovery, research journey” to understand where all this “internalized racism was coming from.” She landed on this phrase “#UnapologeticallyAsian” to describe how she wants to ensure her community doesn’t feel “sorry” for being present in heritage institutions and historical narratives. “I know it’s a larger hashtag that a lot of people use,” she concedes, “but it is a very personal and particular story that had me arrive at this concept that I’ve been building on for almost ten years now.”

Imbued with these ideas, Chow founded the dance company “House of Chow” the following year. Its mission is to “Educate, empower, and unify Asians in and through Hip Hop Dance” through the avenues of performance, workshops, and community building. Their annual gala entitled “#UnapologeticallyAsian” fundraises for this project and celebrates the power of Asian representation in the arts, according to the Asian American Arts Alliance.

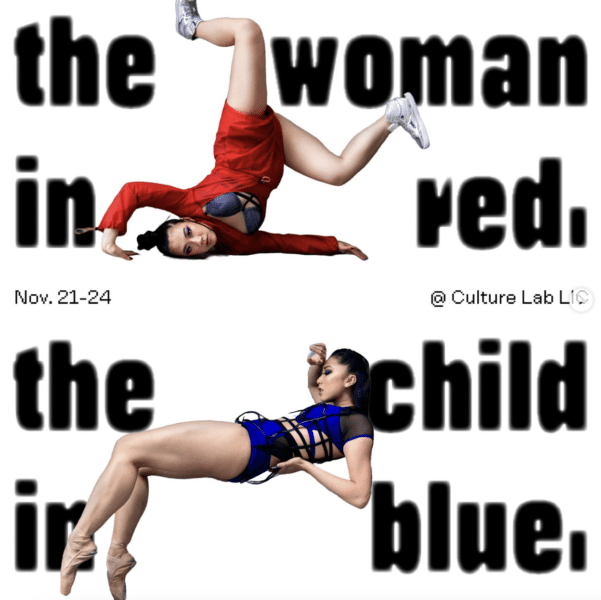

The woman in red and the child in blue contorting themselves. Poster design by Emily Wu.

House of Chow’s upcoming show “The Woman in Red. The Child in Blue” tracks an intergenerational journey of a mother and daughter through the lens of Shamanism, evoking themes of healing and freedom. They will host this new performance in the New Works Festival at Culture Lab, a nonprofit art gallery and space, from November 21st-24rd.

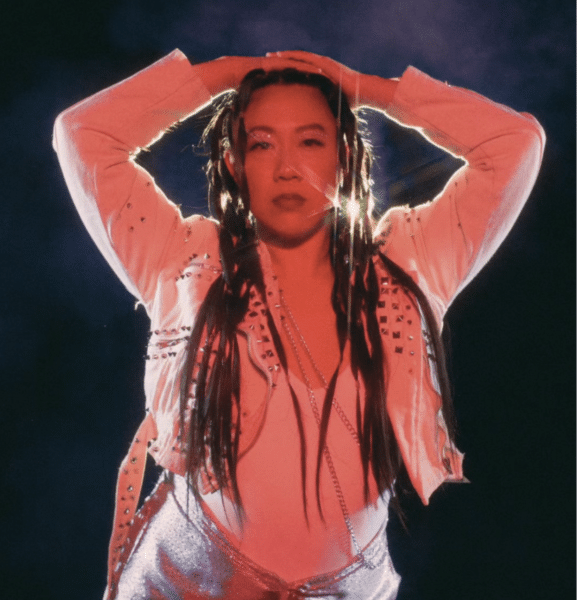

Chow serves as the artistic director of “House of Chow,” creating a futurist vision for the Asian diaspora living in New York City by blending and mending cultural modes of movement — Hip Hop, Asian folk dance, martial arts — while preserving their independent characteristics. She is a decorated professional dancer, choreographer, and first-degree martial artist, with over 20,000 hours (and counting) of dance training. She moved to New York from California in 2005 to join a community of Hip Hop artists in this “Mecca for dance and for culture.”

Chow explains that nothing is accidental or apolitical in her pieces. “Everything that is a personal experience for me, as someone who holds a lot of marginalized identities — being Asian-American, Queer, and first-generation — is just always going to be political in a society like this.”

Emily Wu, a “House of Chow “volunteer and dancer with highlighter-pink streaks in her hair, jests that Chow is a “God” to her, before conceding that she is more of a “mentor in thought and physicality.” Chow “had like twenty years of dance training, and it’s insane. Every time she takes the dance floor, I’m just mind-blown by her technical skills, and her power and strength” gushes Wu.

In the piece, Chow’s choreography blends modalities of movement associated with both the Asian diaspora and Black/Latino American culture. In doing so, she stands at the intersection of a cultural crossroad, trying to navigate a multi-faceted identity. “We’re trying to understand our place in this country: how to belong or not belong,” she elaborates,“How we can access our ancestors and the power of our cultural lineage to understand ourselves extrapolated from a white lens, from white adjacency.”

In order to access the power of her ancestors, she turned to soul-retrieval and ancestral healing — two modalities of Shamanism — with practitioner Langston Kahn. Soul-retrieval occurs when a Shaman journeys to relocate a part of someone’s soul that was lost to a traumatic event. Ancestral healing work seeks to locate the roots of ancestral trauma within lineages to help understand and heal the root of harmful, generationally-entrenched behavioral patterns.

In these sessions, Kahn enters into an altered, trance state with drumming and the guidance of his own helping spirits. Then, he is able to enter into the ancestral plane and access others’ spirits and ancestors. “I’m tracking back in the lineage to where a particular pattern first started, and then I’m describing what’s happening as I’m working with those ancestors to help them resolve and reconcile what’s been unreconciled in their life,” he says.

Chow’s “The Woman in Red. The Child in Blue,” was inspired by this session. Kahn, as the narrator of both the piece and the journey, guides the audience through Yvonne’s lineage as her ancestors work to mend their internal conflicts. The piece is not a reproduction of their session, rather it is a series of experiences and motifs translated into, “the language of dance and of movement, which is her heart language” explains Kahn. “She took different pieces from the healing and wove them together into something that’s bigger than the sum of its parts, that takes the audience through a journey of different types of healing” he explains.

Ella Kennedy, who plays the infamous “Child in Blue” highlights the universality of the piece’s message. The cycle of “adults not expressing their emotions and closing themselves off to their children” can resonate with diverse audiences. “No matter who you are, you’ll find something to empathize with or relate to.”

In Chow’s healing session, “the white lion comes forward as an ally and a helping spirit, which is a traditional spirit in a lot of Chinese cultural traditions and practices,” according to Kahn. In the piece, Chow imagined how the White Lion’s spirit would steward characters through journeys of unexpressed grief.

The role of the White Lion needed to be performed by someone trained in both Hip Hop and Lion Dance, which made I.J Chan the ideal candidate. Chan is a Boston-based, multimodal performer and Lion Dancer. She had casually known Chow for a few years, but they had not yet collaborated together, despite their complementary artistic interests. “The stars kind of aligned and it was exactly the right moment for us to work together,” exclaims Chan.

Lion Dance is a ceremonial form of movement performed to usher in good luck and drive away evil. Women were excluded from Lion Dance for most of its history; the subliminal messaging being that exclusively men bring about good fortune and wealth. In response to more women practicing Lion Dance in the United States and China, she explains: “It’s slowly changing, but it’s just not how we raise our girls in our culture.”

Though “The Woman in Red. The Child in Blue” contains Asian diasporic dances, “House of Chow” is primarily a Hip Hop dance company. Chow describes herself as a “guest in the culture of Hip Hop,” which highlights her unique status as a practitioner of the art form, but outside of the Black and Latino American community that founded and developed it. As an instructor, she teaches her students that “the movement is never detached from the culture” at large. “They’re not just cool moves — I mean, they’re definitely cool moves — but they’re a part of a larger lexicon,” she explains. “I do my best to preserve and highlight those languages in the pieces that I create because they have really strong cultural legacies, and some of that preservation can happen in performance when people get exposed to that kind of language and can start to interact with it in dialogue.”

Jeff Chang, journalist of Chinese/Kanaka Maoli descent and historian of Hip Hop, locates the Asian diaspora within a larger history of Hip Hop and Black Freedom Culture. He notes that Asian American artists have been involved in the Hip Hop scene as early as the 1980s on the West Coast, wherein Latino, Asian, Black, and some white performers, danced together in racially-diverse troupes. “These organic movements start popping up, all of it inspired by these Black and Brown kids in New York City” he recounts.

Black artistic expression has a long history of appropriation and misapplication by outside groups. Chang’s position on Hip Hop’s proliferation in popular media is shaped by over thirty years of reporting and affiliation with its pioneers, like Kool Herc. They imparted to him that “Hip Hop is Black culture, but it’s for the world; it’s something we always wanted everybody to embrace,” he explains. “Unlike these earlier forms of Black music that were co-opted, there’s an insistence within Hip Hop communities that folks understand what the history is.”

“A lot of Hip Hop groups will typically not honor the history,” explained Emily Wu. “People will appropriate Hip Hop without telling the richer history behind it all, and Yvonne is really pushing to go against that.”

Yvonne Huatin Chow posing for the camera in March 2024. Photo by Cirsty Burton.

In this way, Asian-Americans have been enmeshed in the culture of Hip Hop for decades, “allow[ing] us to think about what it means for us all to move together and to get free together” says Chang. “Black freedom culture, through Hip Hop, provided a way to give a lot of Asian American and Pacifica people a voice and a means of being able to express their own identities.”

“Connecting with really strong, confident, self-assured Asian women has been pretty astounding” said Emily Wu. She mentions that she “feels her voice getting louder” and more self-assured, through being a part of this community. “Stereotypes of Asian women typically involve submission; someone who doesn’t talk about their feelings, or talk at all” she explained.“But we have rebelled against stereotypes and boxes that people want to put us in as asian women.”

House of Chow’s newest show, “The Woman in Red. The Child in Blue,” will premiere on Thursday, November 21st at 6:30 PM, followed by performances on the following Friday, Saturday, and Sunday at Culture Lab, Long Island City.

Tags: #UnapologeticallyAsian Ancestral Healing Asian asian diaspora Asian Identity Black freedom culture cultural identity Dance performance Ella Kennedy Emily Wu Hip Hop House of Chow I.J Chan internalized racism Jeff Chang Lion Dance martial arts Mixed Martial Arts New Works Festival shamanism stereotypes Susannah Pittman The Woman in Red. The Child in Blue Yvonne Huatin Chow

Series: Community