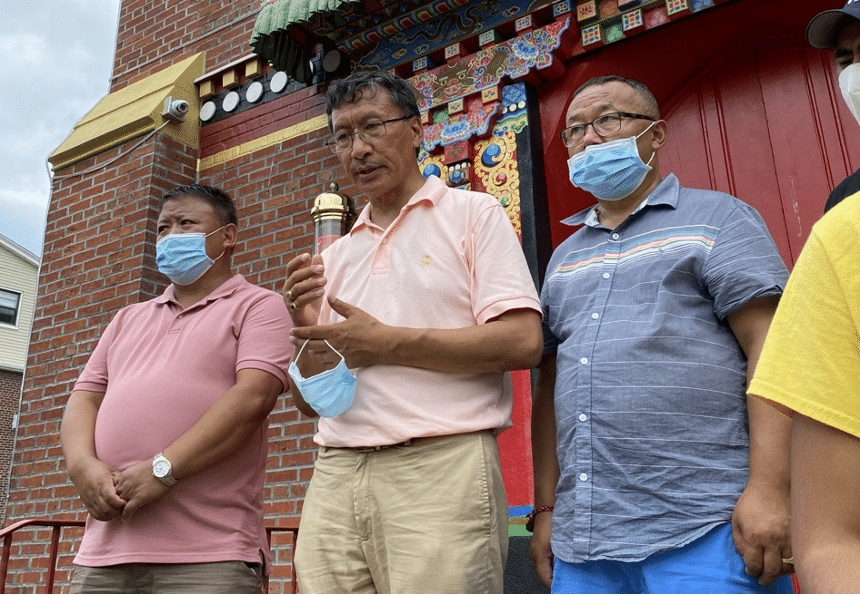

A picture on 125th street of the Apollo Theater, next to a Banana Republic and a Blick art materials. Photo by Abigail Denike.

Maria Lopez sits at a bus stop waiting for the M10 on 125th Street. She is a retired school teacher in her early 70’s who has lived in Harlem her entire life. Maria has witnessed the neighborhood’s changes over the decades. While she welcomes improvements such as new businesses and better public services, she feels conflicted. “I remember when Harlem was the heart of Black culture,” she said. “Now, I barely recognize the place. The rents are so high that my neighbors are being forced to move out.” Maria thinks that the influx of higher-income residents, particularly white people, has led to the decline of Harlem’s unique cultural identity. She fears that rising costs and new developments are making it increasingly difficult for Black families like hers to stay in the neighborhood.

The Great Migration brought in a large number of African American’s to the community of Harlem in the early 1910’s. Since 1916, Harlem has been a historically Black neighborhood. It was the home to the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920’s and artists such as Zora Neale Hurston, James Van Der Zee, and Jessie Fauset brought in the culture. For decades Harlem was a vibrant center for African American culture, art, and history. It’s home to jazz clubs, the Apollo Theater, the recent renovated Studio Museum, and restaurants such as Sylvia’s serving soul food to the community. Local churches with strong religious and civic identities often filled with gospel music.

Harlem now faces challenges as wealthier individuals, many of them white, move into the area. Rising property values and increasing rents often push out long-time residents, who are unable to keep up with the costs. But Harlem has been changing since the 1990’s with an influx of private developers taking ownership of the land. Since the government passed the Third Party Transfer Program it has allowed for a historical shift in the housing market.

Gentrification has been especially harsh for low-income families and elderly residents who have lived in Harlem for decades. For many, the increasing cost of living makes it impossible to remain in the neighborhood that has been their home for generations. Many are forced to relocate to more affordable, outlying areas.

Small, locally-owned businesses are also deeply affected. Esther, another Harlem resident, reflects on the changes in her neighborhood. She reminisces about an old deli she and her sister visited as children. “The owner was so kind—he knew us by name, and it felt like a piece of home every time we stopped by. It broke my heart to see the place up for rent after all those years because he couldn’t afford to stay.”

These mom-and-pop stores have been replaced by Whole Foods, Target, and Sephora. On 125th Street, often referred to as Harlem’s main commercial corridor, the effects of gentrification are especially evident. Once home to a large concentration of Black-owned businesses, the street now features more high-end retail stores, chain restaurants, and commercial offices. The displacement of small, family-run businesses has created tensions between new and long-time resident.

“It’s sad to walk into your own building and barely know who your neighbors are anymore because so many of the people you grew up with had to move due to high rent,” says Esther. “Even small businesses are struggling. There was this gas station I grew up with in the early 2000s, a neighborhood fixture that was replaced by a gigantic condominium building. The worst part? Hardly anyone lives in it—it just sits there, out of place, like it doesn’t belong.”

Tags: 125th Street Abigail Denike community Displacement Gentrification gentrified neighborhoods Harlem Harlem 2024 Harlem Renaissance small business Student Journalism

Series: Community