Mariano Perez has seen a lot of changes in his upper Manhattan neighborhood since he opened the first Dominican bodega, Mi Esfuerzo, on Dyckman Street in 1971. PC Johanni Valerio.

This story was reported and written by a high school student in The City College of New York (CCNY) Early College Program.

In the bodega Mi Esfuerzo, employees talk about the changes they’ve seen on Dyckman Street. Melvyn stood behind the counter with his fellow workers and complained about the new Washington Heights stores. “These new establishments keep appearing around here,” he said. Another employee, Domingo, said, “It seems like it is for the wealthier people.”

Some may catch the irony that the owner Mariano Perez named his store Mi Esfuerzo, or My Resilience, when he opened the first Dominican bodega in the neighborhood in 1971. Every Dominican who lives nearby feels a connection to the bodega and its employees, who always have a game of dominoes going. It reminds them of back home in the Dominican Republic.

But things began to change in this predominantly Dominican-American neighborhood in 2014. That’s when new stores on Dyckman opened and family businesses started to disappear because of increased rent. A Dunkin’ Donuts, a pharmacy where the old parking lot was, and a Starbucks—all new businesses in this Washington Heights neighborhood. In the area from 155th Street to Dyckman, or 200th Street, residential rents also began to rise forcing long-time residents to move.

A study by the CUNY Dominican Studies Institute tracked rising housing costs in Washington Heights/Inwood and the declining presence of Dominicans. It detailed “worrying trends …regarding the lack of affordable housing, skyrocketing rents.” It also found the number of immigrant households declined by 21 percent in fifteen years.

Yolanda Hernandez remembers moving to Washington Heights in 1984. Her home, an apartment first rented by her mom, is the home where she raised her daughters. “Dyckman is a second home for me as a Dominican …. and for other Dominicans, it’s a neighborhood that connects us to our original roots,” she said. Mrs. Hernandez sighed when she talked about the neighborhood changing. She said, “It breaks up the culture here. It brings all these brand name stores while displacing the people who’ve lived here. Politicians should focus on helping the community before helping the new people.”

Back on Dyckman Street Fernando Moronta, another long-time bodeguero (bodega owner), always wears a white, straw pork-pie hat and an oversized sweatshirt. He smiled as he remembered starting out. “It was in 1986 when this bodega opened up. I remember seeing many Dominicans arrive here too, and entering this store hearing the merengue sounds play through my radio,” he said. His smile disappeared when he talked about the changes. “It’s different. There’s still the Dominican culture, but there’s more white people,” he said.

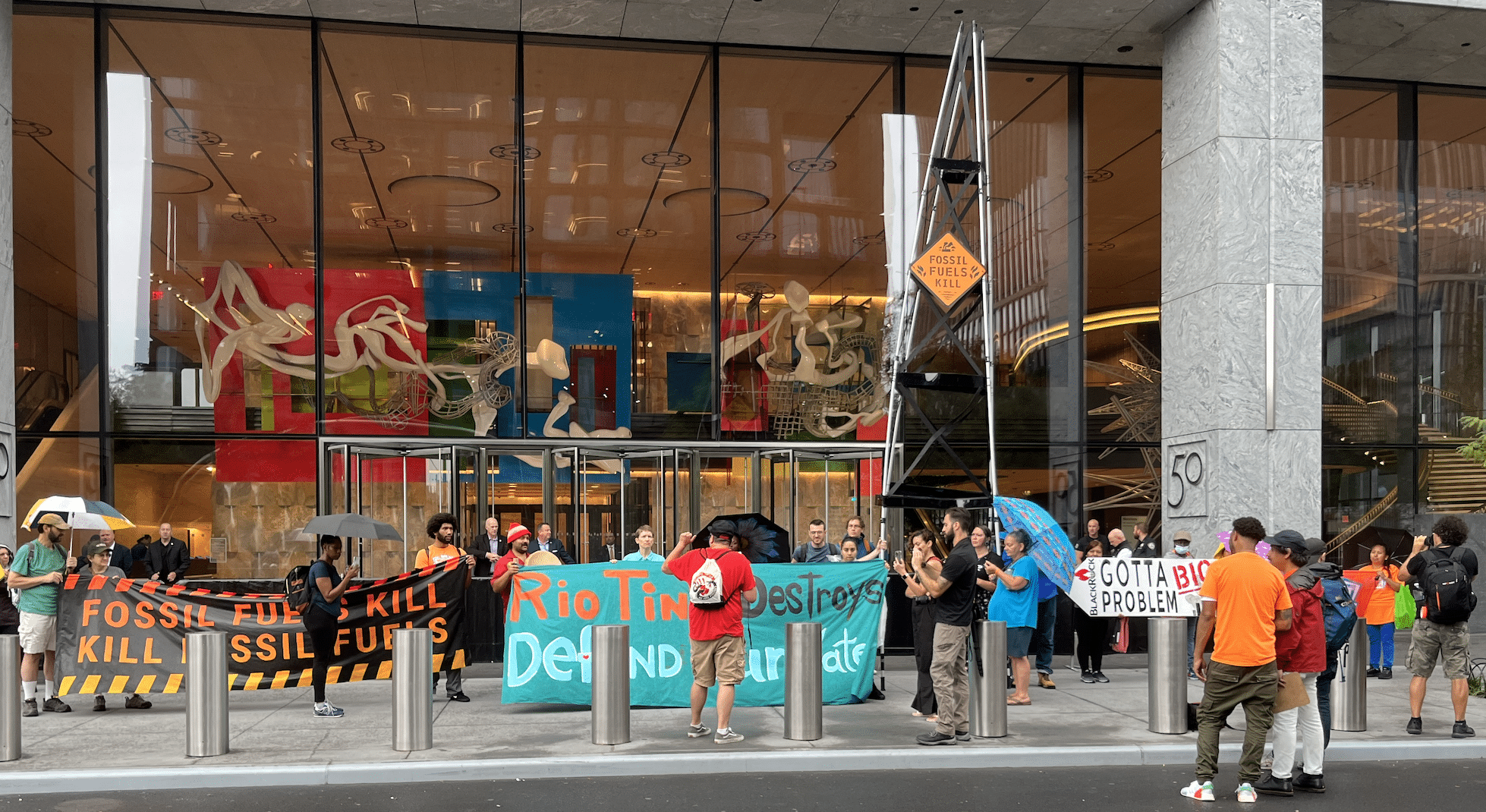

Younger residents whose families have lived here for a long time feel the change. Luz Polanco, a high school senior, moved to Washington Heights from the Dominican Republic about ten years ago. In middle school she began to realize Dominicans felt forced out. “At that time people in my building were protesting against the building that was planned around our neighborhood that [would] raise our rents more,” she said. Everything has become more expensive. Food, rent and staying in the neighborhood costs more. “Most of us Dominicans who work send money and boxes of food, clothes, tools to D.R. We don’t have much to send because bills just stacked up and all the money goes there,” Luz said.

Richi Barua, a high school student whose family moved to Washington Heights in 2012, documented the changes. “I remember doing a photography project on gentrification and when taking pics around the neighborhood I saw these modern apartment buildings, and it’s different from the buildings I live around,” she said.

Paula Fernandez, a high school student originally from El Salvador, moved to Washington Heights in 2011. In just a few years she saw new luxury buildings like you see downtown. Tenants in her building have rented their apartments through AirBnB. “There’s new people literally every week,” she said.

These young people and others have become more and more vocal about gentrification. New York State Assembly Member Carmen De La Rosa noted this on her website: “Young people are driving conversations about gentrification, community preservation and pushing back against the powerful forces looking to move in.”

Luz Polanco thinks about activism. She said, “There are many ways to prevent gentrification to stop hurting our residents. I think that organizing protests and sending requests to the mayor to get his attention on this will help, and also organizing public speeches in our neighborhood with experts on the topic of gentrification can educate more folks about it.”

Tags: Dominican Dyckman Street Early College Program Gentrification Johanni Valerio The City College Academy of the Arts (CCAA) The City College of New York Washington Heights