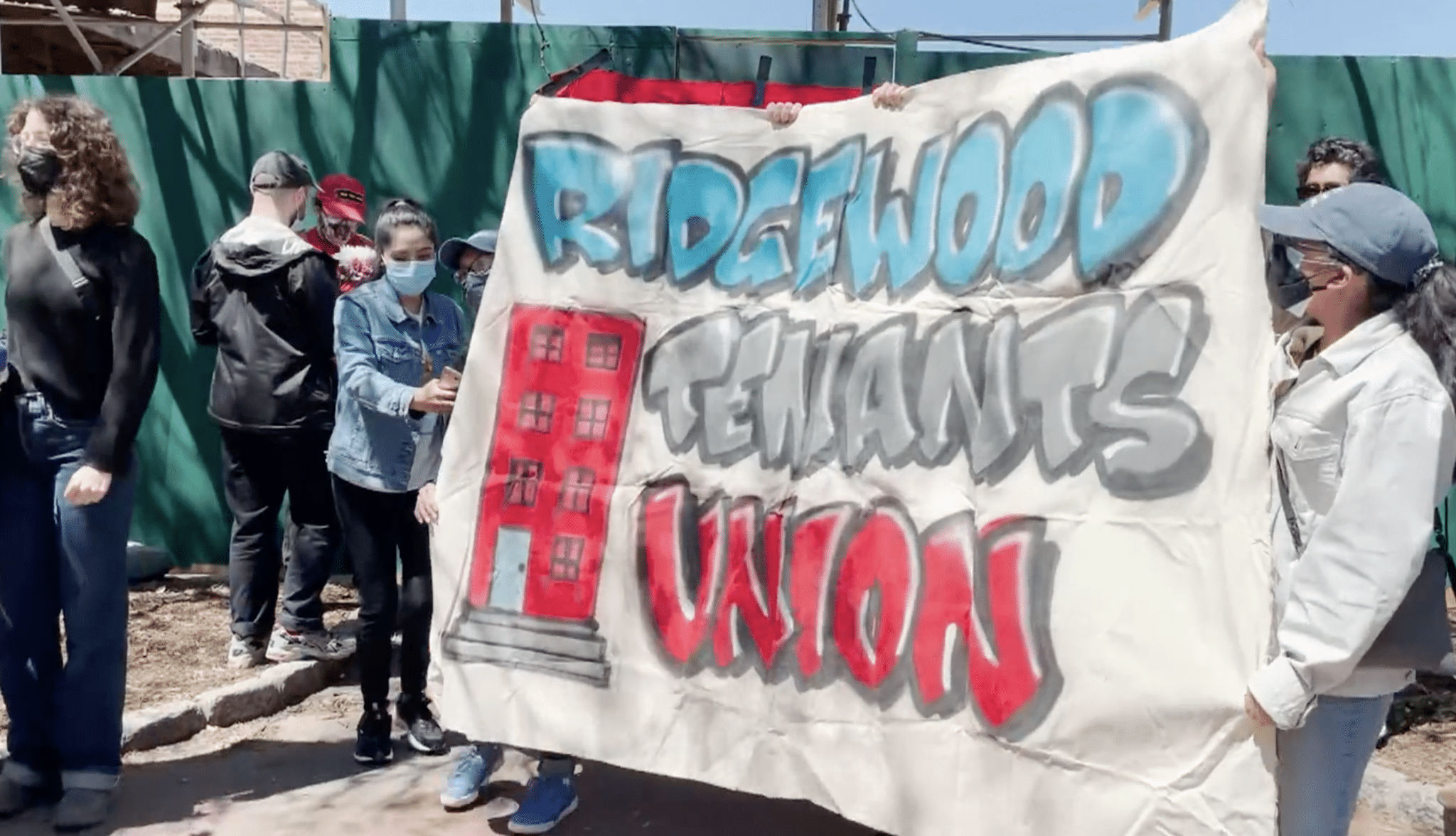

With social distancing guidelines, Haby African Hair Brading is quieter than it used to be, but the customers are glad it's finally open. PC Badiallo Diawara

When Haby Diaoune immigrated from Mali more than twenty years ago, she opened a hair braiding business in Jamaica, Queens. Haby African Hair Braiding supported her family until COVID came along. When she had to close her hair salon because of the lockdown, she worried. “When my business had to close, I was sad because my customers kept calling me every minute because they wanted to braid their hair. But I couldn’t leave to go to their houses, and I didn’t want them to come to mine. I lost a lot of customers during this time,” Diaoune said.

The shop with vibrant orange walls, filled with photos of hair braiding models and prices of different hairstyles, had been a gathering place for Black women and the braiders who helped them manage their hair.

Aisha, a hair braider said, “Customers braid their hair because they want to look pretty, and they like to keep their hair healthy. If their natural hair is out, then it’s easier for breakage to happen.”

Many Black women rely on hair braiding salons, like Haby African Hair Braiding, to help them maintain and protect their hair from damage. Braiding eliminates heat damage from straightening irons and protects against humidity and dryness.

Lisa, who has visited Haby African Hair Braiding about every month for sixteen years said, “When I get my hair braided, it grows. I don’t know how to do my own hair. I always come here to get it done,” she said.

With the shop closed, customers really felt the loss. One shop regular said, “My hair falls out a lot. If I call the hair braider to ask her if she can come to my house, she says no. Now, all of my hair is damaged because I did not braid it for several months.”

During the lockdown, desperate customers felt willing to risk their health and disregard CDC health guidelines to attempt to set appointments indoors—in the homes of hair braiders. Although hair salons were deemed “non-essential,” these salons were essential for Black women.

But some hair braiders refused to put themselves, and their families, at risk for additional income. Aisha, one of the former hair braiders said, “I work as a home health aide. From time to time, I will braid hair for additional income. In the Corona time, my old customers would call me to ask if they can come to my house to do their hair, and I said no. I did not accept that, because I didn’t know if they were going to bring sickness to my home.”

Haby Diaoune reopened her business in June 2020 and was luckier than many other Black business owners. Researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found that the number of operating Black firms fell 56% by May 2020 after the state lockdown, according to Newsday.

Reopening guidelines limit the number of people in a salon to 50 percent capacity. With the reduced numbers, Haby African Hair Braiding, once a fun place, has a different feel to it. Haby said, “It is so empty and quiet now. Before, there was so much noise. All of the hair braiders would speak our language, Bambara, and have fun. There used to be so many customers. It was loud and full, but not anymore.”

Tags: African Hair Braiding Badiallo Diawara Black Businesses Braids cornoavirus COVID-19 lockdown small business owners Small business owners struggling

Series: Coronavirus